Most Prisoners Are Mentally Ill

Can mental-health courts, in which people are sentenced to therapy, help?

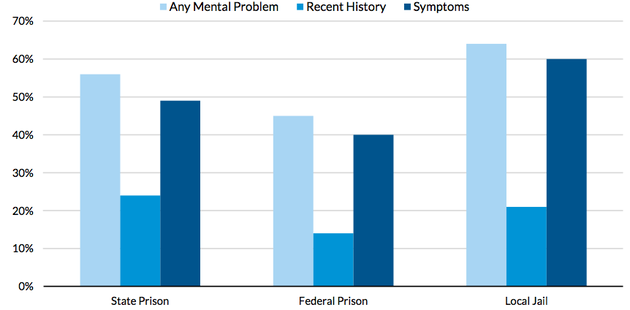

Occasionally policymakers and activists will talk about how the justice system needs to keep mentally ill people out of prisons. If it did that, prisons would be very empty indeed. A new Urban Institute report points out that more than half of all inmates in jails and state prisons have a mental illness of some kind:

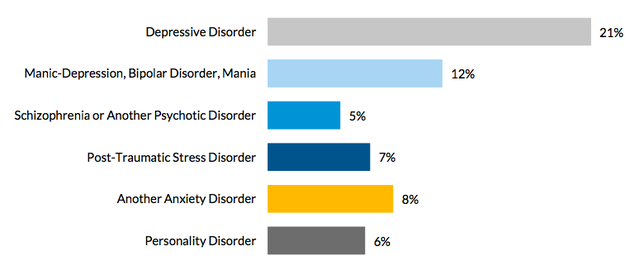

The most common problem is depression, followed by bipolar disorder.

The numbers are even more stark when parsed by gender: 55 percent of male inmates in state prisons are mentally ill, but 73 percent of female inmates are. Meanwhile, the think-tank writes, "only one in three state prisoners and one in six jail inmates who suffer from mental-health problems report having received mental-health treatment since admission."

An increasingly popular program might help thin the ranks of these sick, untreated inmates. What are known as "mental-health courts" have sprung up in a number of states as an alternative to incarceration. A shoplifter who has, say, schizophrenia might be screened and found eligible for mental-health court, and then be sentenced to judicially supervised treatment. These types of courts have expanded rapidly since 2000, and there are now hundreds around the country.

For example, just last week Northampton County in eastern Pennsylvania saw its first case processed in its newly created mental-health court. Here's how the Allentown Morning Call described the process for Kevin Hydro, a depressed alcoholic who broke into an awning store looking for a place to sleep:

Hydro will spend 90 days in an inpatient treatment facility, then transition through social services back into the community.

In total, he'll be under the eye of the county for about two years to ensure he stays on his medications and off of alcohol, said Judge Craig Dally, who heads the court. If Hydro does so, he'll see the trespassing and public-drunkenness charges he faced dismissed altogether.

The courts aren't a cure-all: Two-thirds of them use jail time to punish noncompliance with treatment. The Urban Institute points out that the success of such courts at reducing recidivism has been mixed, but it nevertheless calls them "moderately effective."

It's a promising sign that these are taking off in an era of belt tightening for mental-health resources nationwide. But as the Bazelon Center noted in a recent overview of mental-health courts, it's important that they not become the only avenue for poor, mentally ill people who need help: "There is an inherent risk that any court-based diversion program ... might lead law enforcement officers to arrest someone with a mental illness in the expectation that this will lead to the provision of services."

Currently, though, what we have are prison dorms packed with people who are anxious, depressed, manic or hearing things. As the Bazelon Center puts it:

"No rational purpose is served by the current system."