Abstract

The impact of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) on firm performance is an important issue in organizational research and has been discussed for decades. Only lately, scholars turned their attention towards aspects on an individual level, like the relation between CSR and work satisfaction or work engagement. However, still our understanding of how CSR activities shape organizational outcomes by affecting employees’ motivation remains piecemeal. The present paper adds to this stream by analyzing the impact of CSR activities on employees’ intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Findings indicate that CSR activities both on a firm and on a supra-organizational level have a positive impact on intrinsic motivation, while not affecting extrinsic motivation, i.e. CSR neither fosters nor impedes extrinsic motivation. As a consequence the commitment to CSR can be applied as an effective instrument to induce intrinsic motivation without compromising extrinsic motivation. Furthermore, results point to a non-additive impact of CSR engagement at both levels, which indicates a complex joint impact of CSR engagement on different organizational levels on employees’ intrinsic motivation.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In the past years, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), defined as “context-specific organizational actions and policies that take into account stakeholders’ expectations and the triple bottom line of economic, social, and environmental performance” (Aguinis 2011, p. 855), has been the object of a rich research stream focusing on its impact on organizational performance. However, although several studies found a positive relation between the engagement in CSR and financial performance (e.g., Shen and Chang 2009; see for an overview also Margolis and Walsh 2003; Orlitzky et al. 2003) or between CSR performance and capital constraints (Cheng et al. 2014), other studies failed to identify any positive relations (e.g., Nelling and Webb 2009; see for an overview also Margolis and Walsh 2003). Additionally, the existing studies were criticized for several drawbacks, especially regarding sampling, reliability and validity (Margolis and Walsh 2003). Hence, the relationship between CSR and financial performance remained unclear and scholars have called for a more detailed investigation of the microfoundation of CSR’s impact on organizations (e.g. Christensen et al. 2014). As Aguinis and Glavas (2019, p. 1060) point out: “it is actually individuals who shape CSR and are also affected by a firm’s CSR policies and actions”.

The present paper addresses this call and investigates the impact of CSR on employees’ extrinsic and intrinsic motivation. As scholars stress, particularly the latter type of motivation is of high importance in the context of modern work environments “in which traditional, top-down incentive systems have seemingly reached their limits” (Kuvaas et al. 2017, p. 245). This observation led to a vivid discussion regarding the importance of intrinsic motivation in creative and knowledge-intensive work situations (e.g., Osterloh and Frey 2000; Adler and Chen 2011). However, while scholars argue in this context that firms implement CSR initiatives to positively affect (among other things) their employees’ motivation (e.g. Rupp et al. 2006; Shen and Benson 2014), empirical research on the specific relation between CSR and motivation, and particularly intrinsic motivation, is scarce (cf. for exceptions Mozes et al. 2011; Kim and Scullion 2013; Rupp et al. 2013b; Hur et al. 2018). However, a deeper empirically based understanding of this relation is warranted, as the impact of CSR on employee motivation might be more complicated than expected for the following reasons.

First, the implementation of CSR initiatives can change an organizational target system from a unidimensional, profit oriented system to a multidimensional system comprising a conflict between profit and CSR targets. With respect to human motivation this change in the target system is not trivial. Various theories and growing empirical evidence suggest that human motivation does not only differ in its level (i.e. strength), but equally in its type. As it is highlighted notably in Self-Determination Theory, motivation can be partitioned into intrinsic and extrinsic motivation (e.g., Gagné and Deci 2005). The categorization into intrinsic and extrinsic motivation is based on the question of whether an action is performed for the sake of its consequences, e.g. for a reward, or for its own sake, i.e. for the enjoyment induced by performing the task as such (e.g., Gagné and Deci 2005). Both types can be affected differently and partly contrary by external factors (e.g., Eisenberger and Cameron 1996; Deci et al. 1999; Eisenberger et al. 1999). Thus, the incorporation of CSR initiatives might influence both motivation types differently resulting in behavior that is difficult to predict und thus to manage. Consequently, business practice needs guidance of how CSR activities impact employees’ motivation to better manage their workforce. Yet, so far the impact of CSR initiatives on these motivation types has not been analyzed in detail, as illustrated by the structured literature review by Gond et al. (2017). They mention only one article dealing with the effect of CSR on staff’s motivation, i.e. Kim and Scullion (2013), who draw on McClelland’s motivation theory comprising three main human needs and investigate the impact of CSR on motivation. Recently, Hur et al. (2018) identified a positive impact of CSR on intrinsic motivation, but they did not additionally investigate extrinsic motivation. Thus, the impact of CSR on different employee motivation types still constitutes a largely unexplored topic leading to lacking knowledge in the business context.

Second, so far literature mainly abstracts from a possible joint effect of firms’ CSR initiatives and the promotion of CSR by supra-organizational entities on employee motivation. Yet, the incorporation of such supra-organizational structures is of relevance, as firms never operate in isolation but they are always embedded in overarching structures, like industry associations, which independently of individual firms can promote or hinder CSR initiatives. As employees typically do not only feel part of a certain organization but also as representatives of certain industries or associations of firms, the promotion of CSR on such a supra-organizational level might additionally impact employee motivation. A deeper understanding of possible interaction effects between different organizational levels is warranted, as particularly the current debate about climate change and global pollution draws individuals’ attention more and more towards the regulating power of supra-organizational entities, both in the political but also in the economic context. Environmental problems cannot be solved on a local but only on a national or international basis. Moreover, scandals, like the recent diesel scandal, revealed structural problems not only within single companies but across whole industries. These developments make the importance of supra-organizational entities, that represent such industries, increasingly salient. Consequently, it is very probable, that also employee motivation is affected by such a broadened perspective which leads to a need for a better understanding of the joint effects of CSR activities on different organizational levels. However, so far to the best of the author’s knowledge, research has neglected this aspect in the context of CSR. As the recent comprehensive model by Aguinis and Glavas (2019) illustrates, empirical evidence regarding CSR and employee sense-making covers family, external stakeholders and nationality as extraorganizational factors, but not supra-organizational entities.

Third, literature points to varying relevance of CSR on employees’ psychological states and behavior. For example, Sorensen et al. (2010) suggest that the effect of CSR activities on firm attractiveness might vary between individuals. Ibrahim et al. (2006) found in an empirical study with practitioning accountants and accounting students that the latter actually cared more about ethical and discretionary components of CSR. Consequently, the effect of CSR on employee motivation might vary between employees dependent on their characteristics, like age or social status. Thus, as indicated by the findings of Ibrahim et al. (2006) especially the successful motivation of younger employees could be affected by a firm’s engagement in CSR activities. This is of high relevance for HR practitioners, as Klimchak et al. (2019, p. 1) point out: “Demographic shifts in the labor market require scholars and practitioners to develop a more nuanced understanding of leading and motivating employees”. This holds particularly with respect to young employees as the demographic change leads to a decreasing pool of talented junior employees. Consequently, business practice needs more guidance with respect to factors motivating and thus retaining particularly these employees and a deeper understanding of factors influencing these employees’ motivation is warranted.

The present paper addresses the previously mentioned research gaps: It focuses on the questions of whether only a firm’s activities or also the activities of a supra-organizational entity linked to that firm have an impact on different employee motivation types, and of whether these possible impacts enhance or attenuate each other. Moreover, the analysis focuses on young employees, i.e. the study investigates, whether an impact of CSR on young employees’ motivation can be found.

In contrast to the majority of research on CSR, which uses a cross-sectional methodology (Aguinis and Glavas 2012), the present study draws on an experimental design. This experimental study provides evidence of a positive effect of CSR activities of both the supra-organizational and the organizational level on intrinsic motivation, but not on extrinsic motivation. Moreover, the joint effect of CSR activities of entities at both organizational levels is non-additive. These results add to several research streams, particularly research on enhancing intrinsic motivation while not compromising extrinsic motivation (e.g., Frey 1997; Frey and Jegen 2001; Weibel et al. 2010), research related to a multi-level perspective on antecedents and consequences of CSR (Aguinis and Glavas 2019), research on employer branding and attractiveness (e.g., Bauer and Aiman-Smith 1996; Turban and Greening 1997; Greening and Turban 2000; Schmidt-Albinger and Freeman 2000; Luce et al. 2001; Backhaus et al. 2002; Kim and Park 2011; Lin et al. 2012; Lis 2012; Rupp et al. 2013c; van Prooijen and Ellemers 2015) and research on sustainable human resource management (e.g., Kramar 2014; Ehnert et al. 2016; Järlström et al. 2018).

With respect to business application, the findings provide the following insights: They indicate that CSR initiatives have a positive impact on intrinsic motivation, while they do not compromise extrinsic motivation. As the experience of the last years with monetary incentive systems have shown that it is very difficult to calibrate these incentive systems in a way, that they result in high employee motivation in the long run, the promotion of certain CSR initiatives might be a valuable substitute or complement to these systems.

2 Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1 CSR and the Individual

A rich body of literature discusses the benefits of and the reasons for the adoption of CSR initiatives (cf. for overviews e.g. Carroll and Shabana 2010; Maon et al. 2010; Aguinis and Glavas 2012). Whereas the review by Aguinis and Glavas (2012) indicated that research mainly focused on the institutional and the organizational level and neglected the individual level until 2012 (for a similar observation refer to Morgeson et al. 2013), more recently, research has directed its attention towards the relation between CSR and the individual (e.g., Aguinis and Glavas 2019). Within this research stream different perspectives have emerged: Some scholars focus on how to motivate employees to support a firm’s CSR strategy (e.g., Collier and Esteban 2007; Davies and Crane 2010). Others analyze the influence of firms’ engagement in CSR on employees’ behavior and attitudes towards the firm like firm’s attractiveness as an employer (e.g., Kim and Park 2011; Lin et al. 2012; Lis 2012; Rupp et al. 2013c; van Prooijen and Ellemers 2015) or employees’ job engagement and satisfaction, organizational commitment and identification, turnover intentions, and attachment to the firm (e.g., Peterson 2004; Stewart 2011; Dhanesh 2012; Lee et al. 2012, 2013; Korschun et al. 2014; Brammer et al. 2015).

With respect to the relation between CSR and motivation, particularly, the effect of motivation on the engagement in CSR has been analyzed: Mozes et al. (2011) observed a positive relation between employees’ involvement in CSR activities and their motivation. Thus, this study did not focus on the effect of the adoption of CSR initiatives by the firm on employee motivation but on the effect of the employees’ voluntary engagement in such initiatives on their motivation. On the basis of Self-Determination Theory Rupp et al. (2013a) assumed positive effects of CSR-related relative autonomy, i.e., when employees engage in CSR initiatives due to interest and not due to external pressure, on motivation and approval of their firms’ CSR activities. Rupp et al. (2011) applied Self-Determination Theory to propose a positive link between the satisfaction of particular needs that are central in this theory (the needs for autonomy, competence and relatedness) and organizational members’ advocating for CSR initiatives. Rupp et al. (2013b) picked up this argumentation and underpinned it with a case study. In summary, the previously discussed four articles focus on aspects regarding employees’ motivation to engage in or promote CSR initiatives.

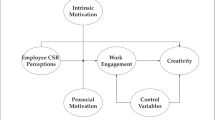

However, literature on a possible impact of firms’ engagement in CSR on employee motivation is very scarce: Balakrishnan et al. (2011) conclude on the basis of experimental findings a positive effect of corporate giving on employees’ motivation. Yet, they test whether their participants were willing to provide monetary resources in the presence of corporate giving. They do not investigate further the motivational dimensions behind this behavior. They just conclude that it should be linked to altruism. In contrast, Kim and Scullion (2013) explicitly draw on McClelland’s motivation theory comprising three main human needs (the needs for achievement, affiliation and power) and investigate the impact of CSR on motivation on the basis of qualitative data, i.e. semi-structured interviews with CSR/HRM managers, high ranked officials, and academics as well as participation and observation. Thus, the authors discuss the relation between CSR and motivation on a more differentiated basis than Balakrishnan et al. (2011). Yet, they do not provide evidence of causal relations between CSR and motivation. Applying a survey, Hur et al. (2018) investigate the impact of employees’ perception of CSR on their creativity and observe a mediating effect of intrinsic motivation between these variables, i.e. they find a positive impact of employees’ perception of CSR and intrinsic motivation. They explain this effect via Self-Determination Theory as follows: “a SDT mechanism suggests that employees’ CSR perceptions motivate them to seek enjoyment, satisfaction of curiosity, self-expression, or personal challenge in the work they do, since a socially responsible firm tends to pursue mutual gains for both society and the company beyond the narrow economic, technical, and legal interests of the firm” (Hur et al. 2018, p. 633). This in turn “affects employees’ intrinsic motivation” (Hur et al. 2018, p. 633). Thus, this study points to a positive impact of CSR on employees’ intrinsic motivation. However, it is survey-based and thus again no causal effects can be inferred, which warrants further experimental research.

The previous discussion indicates, that, although scholars have addressed various questions regarding the link between CSR and motivation, a possible causal impact of CSR initiatives on employees’ extrinsic and intrinsic motivation is relatively unexplored. Just Balakrishnan et al. (2011), Kim and Scullion (2013) as well as Hur et al. (2018) indicate a possible positive impact of CSR on motivation. Yet, they do not provide any evidence with respect to intrinsic and extrinsic motivation and only Balakrishnan et al. (2011) apply a methodology which allows to draw any causal relations, but they do not measure motivation directly. Consequently, these studies indicate a possible impact of CSR on employee motivation in general, but do not provide insights that account for both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. As research on crowding out effects of incentives targeting extrinsic motivation on intrinsic motivation demonstrates (e.g., Frey 1997; Deci et al. 1999; Frey and Jegen 2001; Weibel et al. 2010), particular activities, like incentives or other business factors, can affect both motivation types differently and even contrary. Thus, a differentiated perspective on CSR’s effect on motivation types is warranted to prevent any detrimental effects. In this context, particularly the impact of CSR on these motivation types, and not vice versa, i.e. the impact of motivation on the engagement in CSR activities, is of interest to business practice, as it can provide insights of whether CSR can operate as a valuable motivator.

Moreover, the previously mentioned research focuses on relations between the promotion of CSR initiates on the firm level and that firm’s employee motivation. Yet, as research on sense-making processes in the context of CSR indicates, other levels beside the organizational one should be incorporated into the analysis to improve the understanding of the relations between CSR-related activities on the one hand and effects on the individual level on the other hand (Aguinis and Glavas 2019). Moreover, the literature review by Aguinis and Glavas (2012) indicates, that research on CSR provides a rich body of research regarding the influence of stakeholders, like shareholders, media or activists group pressure, on firms’ CSR activities. In turn, Aguinis and Glavas (2019) discuss the effect of extraorganizational factors, particularly family, external stakeholders and national culture, on employees’ sense-making processes in relation to CSR. Thus, literature addresses the impact of various external factors on firm’s CSR and on its employees’ perceptions of these CSR activities. However, so far literature does not provide insights into possible effects of supra-organizations’ promotion of CSR on employee motivation. Particularly, the recent model by Aguinis and Glavas (2019), which is based on a broad stream of literature, does not discuss any evidence with respect to such effects of supra-organizational entities. However, in the context of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, which—according to Self-Determination Theory (cf. the following section)—are linked to particular perceptional processes related to need satisfaction, this multilevel perspective is of particular importance: As firms are embedded in supra-organizational structures, like industry associations, the promotion of CSR on this level might have an impact on these perceptional processes independently of CSR initiatives on the firm level, because employees can categorize themselves not only as a member of an organization but also as a member of such a supra-organizational entity.

The present paper addresses the mentioned research gaps: It focuses on the effects of CSR initiatives on both employees’ extrinsic and intrinsic work motivation whilst taking into account different organizational levels of CSR engagement and promotion. In contrast to extant literature, it provides evidence regarding causal relations and thereby fosters a better understanding of the microfoundation of CSR’s impact on firm performance. Thereby, it focuses on a particular target group of firms, namely young employees.

2.2 Self-Determination Theory

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) evolved over decades and during that time developed a highly differentiated perspective on human motivation types. SDT provides a basis for both, analyzing the total amount of motivation, i.e. the sum of controlled and self-determined motivation, and the relative weights that are put on the different components.

The starting point of this theory is the categorization into intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, complemented by a status of amotivation, i.e. the absence of any intention for performing an action. The categorization in extrinsic versus intrinsic motivation is based on the degree of instrumentality of behavior (Gagné and Deci 2005): Actions that are performed to receive something like a reward are said to be extrinsically regulated, whereas behavior that is displayed for its own sake because of enjoyment is defined to be intrinsically regulated. Intrinsic motivation is linked to the satisfaction of three innate human needs which are “innate psychological nutriments that are essential for ongoing psychological growth, integrity, and well-being” (Deci and Ryan 2000, p. 229; italics in the original). These needs are the need for competence, autonomy and relatedness. The need for competence is satisfied by positive feedback that induces the feeling of being competent. In the following discussion it is of less importance, as Deci and Ryan (2000) stress, that the satisfaction of this need is relevant for any type of motivation, in contrast the need for autonomy and relatedness are particularly related to intrinsic motivation. The need for autonomy is satisfied by performing self-determined activities. “They are activities that people do naturally and spontaneously when they feel free to follow their inner interests” (Deci and Ryan 2000, p. 234), i.e., for these activities the perceived locus of causality (de Charms 1968) is internal, which in turn satisfies the need for autonomy. Finally, according to Deci and Ryan (2000) also the satisfaction of the need for relatedness is of relevance to intrinsic motivation, albeit they stress, that this need is less important than the other two needs. Yet, “a secure relational base appears to provide a needed backdrop—a distal support—for intrinsic motivation, a sense of security that makes the expression of this innate growth tendency more likely and more robust” (Deci and Ryan 2000, p. 235). Thus, in this context, “[r]elatedness refers to the desire to feel connected to others—to love and care, and to be loved and cared for” (Deci and Ryan 2000, p. 231). As a consequence, work contexts, in which employees perceive their employer as caring for their interests, foster a feeling of relatedness, which satisfies the need for relatedness. This provides the ground for intrinsic motivation to flourish. Consequently, this need is of particular interest in the present context, as the promotion of CSR in organizational entities in which employees operate, can provide exactly this secure relational base which according to Deci and Ryan (2000) fosters the development of intrinsic motivation.

SDT also presents a differentiated perspective on extrinsic motivation, which is categorized in several types dependent on the degree of internalization: In case of external regulation an action is performed due to external contingencies and it is caused purely externally, i.e. individuals act to receive a reward or to avoid punishment (Deci and Ryan 2000). In case of introjected regulation contingencies also play an important role, however, they are not administered externally, but they are exercised by the individuals themselves, like the feeling of guilt, shame or pride (Deci and Ryan 2000). Identified regulation comprises the acceptance of the value of an action and thus the identification with that action (Deci and Ryan 2000). Finally, integrated regulation is self-determined, i.e. “people have a full sense that the behavior is an integral part of who they are, that it emanates from their sense of self and is thus self-determined” (Gagné and Deci 2005, p. 335). Consequently, these extrinsic motivation types can be categorized along a continuum between fully externally controlled and self-determined (autonomous) (Deci and Ryan 2000).

The transitions from one extrinsic category to the other and from extrinsic integrated regulation to intrinsic regulation are very smooth, e.g. if behavior emanates from one’s sense of self, it often is accompanied by a feeling of enjoyment. However, the difference between externally controlled extrinsic motivation on the one hand and intrinsic motivation on the other hand is very large. To get a clear notion of possible differences in the effects of CSR on motivation types, the following analysis focuses on these two types. Thus, in the following sections the term extrinsic motivation only encompasses those parts of motivation which can be attributed to externally controlled extrinsic motivation. Moreover, it concentrates on the employees’ general motivational level within their work situation and not on the motivation to perform a certain task.

2.3 Motivation and Firm CSR

According to the early version of Carroll’s CSR-model from 1979 firms’ social responsibility can be categorized into four types: The first type comprises the “responsibility to produce goods and services that society wants and to sell them at a profit” (Carroll 1979, p. 500), i.e. firms have an economic responsibility. However, firms should perform these economic activities within the boundaries of the legal system, i.e. they also have a legal responsibility. Beside these codified rules in the legal system, firms additionally are confronted with ethical norms leading to their ethical responsibility. Finally, firms can engage in social activities that are not expected by society from them. “These roles are purely voluntary, and the decision to assume them is guided only by a business’s desire to engage in social roles not mandated, not required by law, and not even generally expected of businesses in an ethical sense” (Carroll 1979, p. 500), i.e. the firm also can engage in activities linked to discretionary or philanthropic responsibility (Carroll 1991). Carroll (1991) arranged these four categories along a pyramid with the economic responsibility at the bottom and the philanthropic one at the top. Legal responsibility constitutes the second and ethical responsibility the third layer. Whereas the separation into these four categories or layers suggests four separable categories, Carroll (2016) stresses, that this pyramid should not be seen as a sequence of responsibilities, where the lower layer has first to be fulfilled, before the next one can be addressed. The pyramid is rather a unified whole (Carroll 2016), i.e. in order to fulfill their responsibility, firms should implement all four parts. However, the four categories are affected by different societal forces, as the following discussion illustrates: The adoption of economic and legal responsibility is fostered by external pressure on the firm, because an unprofitable firm and a firm that constantly disobeys legal restrictions cannot survive in the long run, as there are clear mechanisms to terminate its business. In contrast, the demonstration of ethical and philanthropic responsibility is more voluntary and its disregard might not have strong consequences. This is particularly true, if the consequences of unethical behavior are rather distant to employees or consumers, as the minor impact of unethical business activities in the fashion industry on consumer behavior shows. Moreover, unethical behavior is also accepted by large parts of the population, if they benefit from this like very low prices, as the continuous disobeying of animal rights in the meat production shows. Due to this more voluntary character of ethical and voluntary philanthropic responsibility, firms have more degrees of freedom to fill them with live and therefore, can shape them more individually. Consequently, although the four categories form a unified whole according to Carroll, in order to improve the understanding of the impact of CSR on staff’s motivation, they have to be analyzed separately to more precisely elaborate on their individual impacts. To provide a first building block to this differentiated understanding, the present study focusses on the ethical and discretionary responsibilities. Moreover, it addresses both jointly because “it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between ‘philanthropic’ and ‘ethical’ activities on both a theoretical and practical level” (Schwartz and Carroll 2003, p. 506). As previously stated, while the economic dimension follows economic reasoning and the legal dimension is based on written rules, both the ethical and the philanthropic dimensions are guided by rules that are unwritten, partly implicit and more difficult to capture. These characteristics hamper a clear delimitation of the two categories and their precise separation. In turn, these difficulties to separate both dimensions clearly from each other can lead to problems with regard to persons’ perceptions in this context. As a consequence, a clear separation of the effects of both categories on motivation is impeded. Thus, a joint investigation seems warranted in order to avoid misleading research findings resulting from an artificial separation.

In order to derive a possible effect on intrinsic motivation, one has to focus on possible impacts of CSR on the need for relatedness. Rupp et al. (2006) indicate that corporate engagement with society can operate as a signal for its satisfaction as it indicates to employees “that their organization also has concern for them and they may therefore be able to have their interests met, thus satisfying their need for control” (Rupp et al. 2006, p. 540). Similarly, Aguilera et al. (2007) point to such a deontic signal of CSR, i.e. employees look how the organization treats others and from this conclude how the organization might treat them. Consequently, a socially engaged organization is perceived as caring for both, internal and external people, and therefore provides fair conditions also for its employees. Second, Rupp et al. (2006) discuss corporate engagement into society also as a way to enhance positive relations between a corporation and society. “Employees will turn to CSR to assess the extent to which their organization values such relationships” (Rupp et al. 2006, p. 541). In sum, both the signal of caring and the effort to establish positive relationships between a corporation and its environment indicate a secure relational base which Deci and Ryan (2000) stress to be an important background for intrinsic motivation to flourish. Therefore, firms engaging into CSR signal the will to care also for their employees and to establish an atmosphere satisfying the need for relatedness.

Moreover, companies who care for their stakeholders, and thus also their employees, typically also try to establish positive material work conditions, including paying fair salaries. As the previous discussion of SDT illustrates, extrinsic motivation is induced by pure instrumentality and characterized by an external locus of causality. Thus, employees who are particularly regulated by this type of motivation constantly scan their environment for possibilities to receive a reward or for the danger of losing such a reward. Consequently, the signal of caring should also positively affect extrinsic motivation, as employees expect to be treated fairly and to receive fair and adequate salaries. In sum, based on the previous argumentation the following effects on motivation are hypothesized:

Hypothesis 1

The perception of a firm’s engagement in ethical and philanthropic activities enhances its employees’ intrinsic motivation.

Hypothesis 2

The perception of a firm’s engagement in ethical and philanthropic activities enhances its employees’ extrinsic motivation.

2.4 Motivation and Supra-organizational CSR

As discussed in the previous section, the promotion of CSR can serve as a signal to foster positive relations with stakeholders and to establish an atmosphere of caring. Firms often form part of supra-organizational entities which are founded to increase the impact of single firms by e.g. representing whole industries or particular types of firms, like medium sized companies. Employees, who work for a firm, that is member of such an entity, are also affected by these entities’ activities. Thus, that entity’s promotion of CSR as well fosters an atmosphere of caring and signals the will to establish positive relations, which should, albeit possibly weaker, satisfy employees’ need for relatedness. In turn, this should affect employees’ intrinsic motivation positively. Additionally, this signal for caring also indicates a will to foster a fair treatment of the member firm’s employees and to induce reasonable payment and adequate other material equipment, which positively affect extrinsic motivation. Therefore, the following hypotheses can be derived.

Hypothesis 3

The perception of the promotion of ethical and philanthropic activities by a supra-organizational entity of which a firm is a member enhances the intrinsic motivation of that firm’s employees.

Hypothesis 4

The perception of the promotion of ethical and philanthropic activities by a supra-organizational entity of which a firm is a member enhances the extrinsic motivation of that firm’s employees.

2.5 Motivation and the Interaction between Supra-organizational and Firm CSR

While the previous hypotheses focus on effects of CSR on employee motivation in isolation on both levels, the joint presence of CSR on both levels might result in somewhat different effects. If the supra-organizational entity fosters CSR and thus asks its members to implement it, the engagement into CSR activities by a member firm might be perceived as being less voluntary as in case of a CSR engagement of a firm, that is not part of an entity which stresses the importance of CSR. Consequently, employees might perceive the engagement of the earlier firm as stemming less from an inherent will to establish positive relations with stakeholders and thus also its employees, but rather as an adaption to industry-requirements. This perception should reduce the satisfaction of the need of relatedness compared to a firm which completely voluntary engages in CSR. Consequently, the impact of a simultaneous commitment of a firm and a supra-organizational entity to ethical and philanthropic activities on intrinsic motivation should be lower than expected if one adds the two single effects. A similar effect should be observed with respect to extrinsic motivation, as again a less voluntary engagement into CSR hampers the perception of a carrying employer that also will provide employees voluntary with fair salaries and good material conditions. Thus, in both cases one should observe an interaction effect. This leads to the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 5

The perception of a joint commitment to ethical and philanthropic activities at the firm and at the supra-organizational level has a non-additive effect on intrinsic motivation.

Hypothesis 6

The perception of a joint commitment to ethical and philanthropic activities at the firm and at the supra-organizational level has a non-additive effect on extrinsic motivation.

3 Method

3.1 Data Collection

A vignette experiment was conducted to test the hypotheses (cf. for a detailed discussion of this research method e.g., Alexander and Becker 1978; Wallander 2009), i.e. the subjects received a situational description and were asked to answer several questions based on this description. A 2 × 2 between-subjects-design was applied, i.e. each subject received only one situational description. Between-subjects-design was selected, as the situational descriptions are quite long and the presentation of multiple situations could quickly result in effects of fatigue. Sample vignettes were rated for ecological validity by researchers at a German university. The researcher were experienced in research on management controls, diversity management and motivation. Additionally one practitioner looked through the vignettes. He was in a higher management position and was trained in management controls and risk controlling. Feedback indicated no need for significant changes to the vignettes.

The participants for the main study were graduate students in business administration. Data was collected at the beginning of a session (during teaching time) in a management control course, which was given in June 2016 at a German university. The experiment was conducted in a session before ethical issues in management control were further discussed in class. The participation was voluntary and it was not rewarded (e.g., by grading or else). The vignettes were administered randomly at the beginning of the session, i.e. each participant received one vignette. The experiment was performed with the group as a whole to assure constant conditions for all participants in terms of time of day, temperature, weather, etc., because such circumstances might influence the level of intrinsic motivation and then lead to confounding effects. Participants were explicitly told not to communicate with each other and the experimenter (author) controlled visually that they complied with this rule. Moreover, the students were told that there are no right or wrong answers. They were promised full anonymity and confidentiality, and they were told that their individual responses would not be shown to their teachers or other students. It was thought that this anonymity would minimize social desirability response bias. To inhibit any bias from detailed information regarding the aim of the study, up front the students were only told that the study was conducted to get a deeper understanding of decision processes in companies. They were also told that the content of the study was linked to the following lecture topics, i.e. ethical aspects of management control and research methods in management control research. After filling in the questionnaires, the students received additional information about the purpose of the study, its hypotheses and its relation to the succeeding topics of the course.

Graduate students were selected as subjects as they can be seen as representative for young employees because in Germany it is common practice that students start working as student trainees or student apprentices already during the time of their undergraduate studies.

Since each vignette contained two situational variables of which each could have one of two states, there were 2 × 2 = 4 different vignettes. Each vignette was generated 30 times and included in a questionnaire. Hence, in total 120 questionnaires were distributed to conduct the present study. Each test person received one vignette. All questionnaires were handed back. Six questionnaires were filled out not at all or in large parts incompletely and therefore had to be excluded from the sample. Hence, 114 questionnaires were used in the study, which equals a response rate of 95%.

3.2 Experimental Design

Each questionnaire comprised 5 pages (including title page and the situational descriptions) and was structured as follows: (1) title page with information, how to work through the questionnaire, (2) newspaper article, (3) question regarding this article to induce deep cognitive processing, (4) description of a firm, (5) measurement of motivation, (6) measurement of understandability and traceability of description, (7) manipulation checks, (8) questions regarding age, sex and work experience.

To test for the impact of a supra-organizational entity’s commitment to CSR, the participants first read a short, fictive newspaper article that provided a report regarding a conference held by a fictive German association representing small and medium-sized firms. This conference either dealt with the need of sustainable management and social engagement (active commitment to CSR, CSR1 coded as 1), like the implementation of ecological production processes and the integration of minority groups, or it discussed the need for modern performance measurement systems abstracting from any CSR engagement (no active commitment to CSR, CSR1 coded as 0). This manipulation was explicitly not designed in a way, that the test subjects were confronted with an association that either offensively fosters CSR or offensively neglects the importance of CSR, because such a manipulation could be seen as unrealistic: Currently an explicit devaluation of CSR activities by such supra-organizational entities is not accepted in society, at least in the cultural environment of the test subjects. Thus, for strategic reasons a devaluation of CSR would not be communicated by such an association. To prevent any effects of length, both reports (written in German) had the same length in terms of number of characters, i.e. both contained 939 characters (including blank spaces). Appendix A presents both text cues translated into English. After reading this article, the participants were asked to summarize the content of the presented text in one or two sentences to facilitate its deeper cognitive processing.

Thereafter, test subjects were asked to read a situational description. They were instructed to imagine that after their successful graduation as master students they had started to work for a medium-sized firm. To instill a certain level of intrinsic motivation this firm was described positively, i.e. the situational description was designed in a way that allowed the emergence of intrinsic motivation (Kunz and Linder 2012b). Moreover, the situational description also contained text cues that pointed to performance-based promotion possibilities to address the extrinsic part of motivation. Appendix B provides a translation of the text cues. Within these descriptions the extent of the firm’s commitment to CSR was also mentioned. The firm either stressed economic goals and followed the legal standards but did not engage in any further CSR activities (no firm commitment to CSR, CSR2 coded as 0) or the firm exhibited an active commitment to ethical and philanthropic activities beyond following economic goals and obeying legal standards (active firm commitment to CSR, CSR2 coded as 1). Again to prevent any effects of length, both text cues had a similar amount of characters (no firm commitment = 548 characters including blanks, firm commitment = 544 characters including blank). These situational descriptions were followed by a questionnaire containing items to assess the dependent and the control variables as well as manipulation checks (cf. the following sections).

3.3 Measurement of Motivation and Interaction Term

In order to measure the degree of the different motivation types, the Motivation at Work Scale developed by Gagné et al. (2010) was translated into German by the author, adapted to the present study and combined with a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (do not agree at all) to 7 (fully agree). The instrument contains items for all motivational types suggested by SDT. The following analysis focuses on the items for intrinsic motivation (three items) and extrinsic motivation (three items) (see Appendices C and D). For further analysis the items of each variable were averaged. Extrinsic and intrinsic motivation have a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.60 and 0.79, respectively. The items of the two motivation types were introduced into a principal component analysis with varimax rotation. Applying the Kaiser criterion resulted in two factors explaining 35.79% (intrinsic motivation) and 28.76% (extrinsic motivation) of total variance (after rotation), where the items for intrinsic motivation exhibited loadings of at least 0.77 with respect to one factor, and the items of extrinsic motivation exhibited loadings of at least 0.62 regarding the other factor.

To investigate H5 and H6 an interaction term was calculated, where the association’s commitment to CSR was coded as 1 and no commitment as 0, and the firm’s commitment to CSR was coded as 1 and no commitment as 0.

3.4 Control Variables and Manipulation Checks

The study contained two control variables aiming at how ecologically valid participants judged the vignettes they received. The two items were taken from extant literature (Kunz and Linder 2012b; Kunz 2015) and measured on 7‑point Likert scales with response alternatives ranging from 1 (very poorly/very difficultly) to 7 (very well/very easily) (please refer to Appendix E for the exact wording of the items). The means of the responses to the two items were 5.97 and 5.71, respectively, indicating that the participants understood the vignettes very well and could put themselves easily into the situation. Furthermore, participants were asked to indicate their sex and age. Regarding sex, there was an equal split, i.e. 57 participants were female and 57 were male. The mean of age was 24.7 years and its median 24 years. Another item was added to control for the potential influence of work experience on the answers. It was operationalized as an open-ended question on months of work experience in paying jobs (cf. Appendix E). The mean of work experience was about 34 months and its median was 25 months.

To examine whether the subjects correctly understood the presented situations, manipulation checks were introduced. The subjects received several statements to which they were asked to indicate their agreement on a scale of 1 (do not agree at all) to 6 (fully agree). Appendix F provides the manipulation checks and Table 1 contains the descriptive statistics of the answers to the manipulation checks regarding the constant text cues, where 6 was always the correct answer. In one questionnaire the item regarding work climate was not answered. But as this questionnaire contained all answers with regard to the dependent and the control variables, it was kept in the sample, and thus, the statistics on work climate are based on a sample of 113 questionnaires. The means show that the subjects understood the presented situations on average very well.

With respect to the experimental variables three manipulation checks were applied. Regarding the variable CSR1 two manipulation checks were administered. The first item tested, whether the subjects think that the newspaper article deals with the importance of modern performance measurement systems for small and medium-sized firms. In case that the article actually deals with this topic the mean is 4.84 (standard deviation = 1.27), on the opposite case the mean is 2.39 (standard deviation = 1.38). In one questionnaire this item was not answered. But as this questionnaire contained all answers with regard to the dependent and the control variables, it was kept in the sample, and thus, the statistics on this item are based on a sample of 113 questionnaires. A two-tailed t‑test was significant (p < 0.001, t = 9.82), as well as the Mann-Whitney-U-test (p < 0.001, Z = −7.19).

The second item examined whether the subjects think that the newspaper article deals with the need of sustainable management and social engagement for small and medium-sized firms. In case that the article actually deals with this topic the mean is 5.04 (standard deviation = 1.53), on the opposite case the mean is 2.38 (standard deviation = 1.65). In three questionnaires this item was not answered. But as they contained all answers with regard to the dependent and the control variables, they were kept in the sample, and thus, the statistics on this item are based on a sample of 111 questionnaires. A two-tailed t‑test was significant (p < 0.001, t = −8.83), as well as the Mann-Whitney-U-test (p < 0.001, Z = −6.64).

The third item investigated whether the subjects think that the presented firm is committed to CSR. The manipulation check yielded in case of no commitment a mean of 1.39 (standard deviation = 0.78), and in case of commitment to CSR a mean of 5.53 (standard deviation = 0.83). In one questionnaire this item was not answered. But as this questionnaire contained all answers with regard to the dependent and the control variables, it was kept in the sample, and thus, the statistics on this item are based on a sample of 113 questionnaires. A two-tailed t‑test was significant (p < 0.001, t = −27.36), as well as the Mann-Whitney-U-test (p < 0.001, Z = −9.49).

As mentioned above several questionnaires did not contain answers to all manipulation checks. In detail, in three questionnaires one item was not answered and in one questionnaire three items were not answered. Moreover, the two manipulation checks dealing with CSR1 exhibited slightly less favorable results with respect to the lower pole (means of 2.39 and of 2.38, respectively) than the manipulation check regarding CSR2 (mean = 1.39).

4 Results

Table 2 provides a detailed summary of the descriptive statistics of the variables. Table 3 shows the correlations between the variables. Intrinsic motivation exhibits a significant correlation with CSR1, understandability, and traceability (p < 0.01), whereas extrinsic motivation significantly correlates with understandability (p < 0.01). Both dependent variables do not correlate significantly with each other. With respect to the control variables statistically significant correlations can be observed between understandability and traceability, as well as age and work experience (p < 0.01). However, these correlations are in a range, which does not indicate material problems with multicollinearity. Table 4 provides the mean outcomes of the four treatments with respect to intrinsic and extrinsic motivation.

Regressions with robust standard errors were applied for the lack of homoscedasticity of several regression models (i.e., the Breusch-Pagan test gets significant in those models with intrinsic motivation as dependent variable). In all models the maximum VIF lies below common thresholds, further reinforcing the impression gained from the descriptive statistics that multicollinearity should not taint the findings.

Three regression models are calculated for testing the hypothesized relations. The first model includes only the control variables. As sex does not exhibit a significant effect in the regressions and does not correlate with any variable, this control variable is not introduced. The second regression model additionally contains the independent variables CSR1 and CSR2 to test Hypotheses 1–4. In the third regression model the interaction terms to study Hypotheses 5 and 6 are added.

Table 5 summarizes the results of these regressions. Regarding intrinsic motivation both the association’s and the firm’s commitment to CSR exhibit a significant positive main effect, whereas with respect to extrinsic motivation no significant main effects are observed. Consequently, with respect to intrinsic motivation regression model a2 supports Hypotheses 1 and 3, while regarding extrinsic motivation Hypotheses 2 and 4 have to be rejected on the basis of model b2.

However, the main effects on intrinsic motivation are further qualified by the interaction of both variables. In case of intrinsic motivation a significant negative interaction can be observed, whereas in case of extrinsic motivation the interaction is insignificant. To better interpret the results of regression model a3 the treatment in which no commitment to CSR by the association is mentioned (CSR1 coded as 0) and in which the firm does not engage in CSR activities (CSR2 coded as 0) is defined as base line. With respect to intrinsic motivation the following aspects can be observed: The introduction of the firm’s commitment to CSR (CSR2 coded as 1) increases the dependent variable by 0.83 compared to the base line, whereas the commitment to CSR by the association (CSR1 coded as 1) has an effect of 1.02. The combination of an association’s and a firm’s commitment to CSR leads to a total increase of 1.02 + 0.83 + (−0.90) = 0.95. Thus, there is a non-additive effect of the commitment to CSR at both organizational levels. This supports Hypothesis 5. In contrast, Hypothesis 6 cannot be supported, as there is no significant effect on extrinsic motivation at all.

5 Robustness Checks

As in case of intrinsic motivation one outlier and in case of extrinsic motivation two outliers appeared in the third models, they were further analyzed applying a version of robust regression implemented in Stata as rreg. The results do not change materially. As indicated in Table 6 with respect to extrinsic motivation CSR1, CSR2 and CSR1 * CSR2 are insignificant, as well as traceability and age, whereas understandability and work experience are significant (p < 0.05). With respect to intrinsic motivation the previously found result regarding the interaction term is also supported by this analysis with BCSR1 = 0.78 (p = 0.001), BCSR2 = 0.76 (p = 0.001) and BCSR1 x CSR2 = −0.75 (p = 0.016).

Moreover, as it is debated, whether controls should be introduced at all in the analyses of experiments, also the results of the regressions with robust standard errors without controls were tested (see Table 7). In case of intrinsic motivation the coefficients have the following values in the third regression model: BCSR1 = 1.04 (p < 0.001), BCSR2 = 0.68 (p = 0.022) and BCSR1 x CSR2 = −0.78 (p = 0.029). In case of extrinsic motivation the following results can be observed in the third model: BCSR1 = 0.04 (p = 0.853), BCSR2 = −0.24 (p = 0.329) and BCSR1 x CSR2 = 0.18 (p = 0.611). These results indicate that the qualitative results do not change when leaving the controls out.

6 Discussion

The previous analysis investigated the effects of supra-organizational entities’ and firms’ commitment to ethical and philanthropic activities on employees’ intrinsic and extrinsic work motivation. The analysis showed, that the commitment to these CSR activities at both levels exerts a positive impact on intrinsic motivation. Additionally, an interaction effect of CSR activities at both levels on intrinsic motivation could be observed. This result indicates a non-additive impact of such activities at both levels.

In the previous analyses it turned out, that on the one hand, CSR activities exert a positive effect on intrinsic motivation, whereas extrinsic motivation is not affected. On the other hand, the presence of CSR activities at one organizational level or at both organizational levels at the same time had in terms of the absolute effect size a similar impact on intrinsic motivation, i.e. the single effects are non-additive. This observation points to the possibility that the promotion of CSR on the supra-organizational level makes the engagement in CSR on the firm level appear less voluntary which in turn compromises its positive effect on intrinsic motivation. These findings provide valuable insights to research dealing with the impact of CSR activities on employee motivation in several ways.

First, the present findings confirm Hur et al.’s (2018) observation with respect to a positive effect of CSR on intrinsic motivation. Thus, they indicate that CSR positively affects exactly that part of motivation which is rather difficult to be influenced positively by monetary incentives, as the large body of research regarding the motivational crowding out effect exhibits (e.g., Frey 1997; Frey and Jegen 2001; Weibel et al. 2010). At the same time, in the present study CSR does not have any effect on extrinsic motivation, which also means that it does not exert a negative effect on this motivation type, which could possibly offset the positive impact on intrinsic motivation. In the present paper, it was argued for a possible positive effect of CSR on extrinsic motivation, as it constitutes a signal of caring to the employees which conveys the will to also share resources with them. However, as Balakrishnan et al. (2011) point out, the engagement in CSR, in their case corporate giving, could also result in a negative signal to employees of reducing “the size of the pie to be shared between employer and employee” (Balakrishnan et al. 2011, p. 1889), which would exert a detrimental effect on extrinsic motivation. Yet, the present study does not indicate this effect, i.e. CSR does not induce intrinsic motivation while compromising extrinsic motivation. Consequently, CSR can operate as a valuable motivator.

Second, the results broaden the perspective of what actually activates employees’ intrinsic motivation and to which extension the broader context of an employee’s work environment has to be considered to better understand his/her reactions. So far, research has focused on the influence of a firm’s CSR activities on different psychological and behavioral characteristics of employees, like work satisfaction or work engagement. It also focused on the effect of external factors on firm’s CSR activities (for an overview see e.g., Aguinis and Glavas 2012). Yet, it does not account for the impact of CSR activities of supra-organizational entities, which embed an employer, on employees’ motivation, work satisfaction, etc. The present study indicates, that while the engagement in CSR on both levels has a positive effect on intrinsic motivation, this positive effect is attenuated when both levels jointly promote CSR. The promotion of CSR on the supra-organizational level seems to change the employees’ perception of the voluntary nature of the firm’s engagement in CSR, which reduces its—albeit positive—effect on intrinsic motivation. This finding indicates the complexity of affecting employees’ intrinsic motivation through CSR activities and provides the ground for a call for a much broader perspective on this topic incorporating multiple levels.

Third, the findings can help to enhance both employer branding to recruit talented young staff and organizational processes to retain it, as they point to the engagement in CSR as a possible way to motivate young employees. Thereby, these insights constitute a valuable building block for the research stream focusing on the impact of CSR on employer attractiveness (e.g., Bauer and Aiman-Smith 1996; Turban and Greening 1997; Greening and Turban 2000; Schmidt-Albinger and Freeman 2000; Luce et al. 2001; Backhaus et al. 2002; Kim and Park 2011; Lin et al. 2012; Lis 2012; Rupp et al. 2013c; van Prooijen and Ellemers 2015).

Fourth, the results are related to the growing research stream of sustainable human resource management, i.e. the “adoption of HRM strategies and practices that enable the achievement of financial, social and ecological goals, with an impact inside and outside of the organization and over a long-term time horizon while controlling for unintended side effects and negative feedback” (Ehnert et al. 2016, p. 90). This research stream is relatively new (Wikhamn 2019) and comprises a variety of conceptualizations of sustainable HRM (Kramar 2014; Järlström et al. 2018). As further stressed by Wikhamn (2019, p. 104) “attracting, retaining and developing employees have been emphasized in sustainable HRM research”. Thus, sustainable HRM both is intended to use HRM practices to establish CSR in organizations, but also to provide a sustainable basis to gain a superior work force. The present findings enhance this perspective, by providing evidence that the engagement in CSR to foster well-being in society also enhances (young) employees’ motivation.

Finally, the findings provide an important building block for the understanding of the microfoundation of CSR’s effect in firms. Dhanesh (2014) argues that CSR can be seen as an organization-employee relation management strategy. However, more precisely, Kim and Scullion (2013) point out, firms typically do not implement CSR activities in order to motivate their own employees, but the authors find that “when the businesses ‘assess’ the results of CSR, employee motivation emerges as a major outcome/influence of CSR to organizations” (Kim and Scullion 2013, p. 13). The present results support this observation at least partly, as they show for intrinsic motivation a positive main effect of a firm’s commitment to CSR. Consequently, CSR activities exert positive side effects on organizational outcomes apart of their main purpose, namely fostering societal welfare.

7 Limitations and Conclusion

As any study, also the present one suffers from several limitations which provide avenues for future research. The following aspects deserve particular attention.

First, to check for the robustness of the results, further analyses applying robust regression analysis and regressions without control variables were used. These analyses confirmed the previous results. As a consequence the observed effects can be judged to be statistically robust, albeit that the manipulation checks regarding CSR1 were less favorable than those regarding CSR2. However, the robustness of the findings also has to be judged with respect to the methodological background. As discussed in literature, vignette studies as well as laboratory experiments may suffer from a lack of ecological validity (Linder 2010). In literature, some evidence exists that might put this concern into a perspective (cf. for the following discussion also Kunz 2015). On the one hand, in a meta-analytic study a high correlation of 0.73 was found between effects in experimental studies and field studies (Anderson et al. 1999). On the other hand, in a study regarding corporate entrepreneurship Linder (2010) compared the answers observed in a vignette study to those obtained in a field study. His findings suggest an acceptable degree of ecological validity for vignette studies. Yet, vignette studies should be seen as only one possible way to generate new empirical results. Therefore, the findings presented in this paper should be subject to further testing and methodological refinements using other empirical instruments such as laboratory experiments or field studies.

Second, the applied scale to measure motivation was translated only by the author into German and not back-translated. As the items in this scale are very similar to items used by the author before in other papers (Kunz and Linder 2012b; Kunz 2015), back-translation was not performed. However, this might nevertheless have an impact on the validity of the items.

Third, the study relied on students in the area of business administration. As it focuses on the impact of CSR activities on young employees’ motivation, this sample should be reasonable. However, research on CSR indicates differences regarding the importance that employees of different age put on these activities (e.g., Ibrahim et al. 2006). Therefore, the presented findings should not be generalized to all employees. It might hold especially for younger professionals with an academic background, while more research is needed with respect to older employees and blue collar employees: Older workers might already have had more negative experience with CSR activities, that actually had detrimental effects on their work environment, like unpaid, involuntary overtime to perform any social activities in the name of the firm. They also had more time to make experiences with controversial CSR in firms (Turner et al. 2019), which further shapes their perception of CSR in general. Blue collar workers might have a different socialization and experiential background and, thus, another perspective on the meaningfulness of CSR activities. Additionally, the present study does not provide evidence with respect to whether different types of participants’ work experiences might exert additional effects, which points to a further need for future research. In sum, future research should investigate also these groups and analyze explicitly differences by directly comparing their reactions.

Fourth, the present findings point to the need for further research, as the research design did not allow for the separate investigation of need fulfillment, i.e. the engagement into ethical and philanthropic activities satisfies the relevant needs for intrinsic motivation to flourish, versus selection processes, i.e. persons high in intrinsic motivation might be more attracted by firms and/or industries that engage into ethical and philanthropic activities.

Fifth, the present paper focuses on externally controlled extrinsic motivation. However, as SDT exhibits, extrinsic motivation is a complex construct containing different types of motivation dependent on the degree of internalization. Consequently, future research should apply a more differentiated perspective on them and test the relation between CSR and different types of extrinsic motivation. In this context, one also should mention the interesting finding, that in case of no CSR1 and no CSR2 intrinsic motivation is considerably lower than extrinsic motivation compared to the other cases. This result also provides a starting point for additional research.

Finally, the results also might be affected by external events. When the experiment was conducted, media still was discussing about the diesel scandal. This scandal affected especially VW, but also other car manufactures, which might have increased the salience of CSR on a supra-organizational industry level. Thus, future research also should target the side-effects of such scandals on (prospective) employees’ reactions towards CSR.

As the previous discussion exhibits, the present study, as any outcome of empirical research, is affected by particular limitations. Nevertheless, to the author’s best knowledge, it is the first study to take empirically a multi-level perspective on the impact of CSR on employee motivation. Thereby, it provides important evidence to guide business practice and it prepares the ground for important future research. Particularly it directs attention towards the complex interaction effects of CSR engagement at different organizational levels.

Notes

Translated into English. The original text in the study was in German.

Translated into English. The original text in the study was in German.

Translated into English. The scales used in the study were in German. In the study the items were randomized. The items were taken from Gagné et al. (2010), translated into German and adapted to the study.

The scales used in the study were in German. In the study the items were randomized. The items were taken from Gagné et al. (2010), translated into German and adapted to the study (see below). The presented items are a back translation of the adapted items used in the study.

Within this item “in the long-run” was added, as the participants were put into a situation in which they currently could not assume to have a very high salary, as according to the situational description they just had started their career.

Within this item “in the long-run” was added, as the participants were put into a situation in which they currently could not assume to have a very high salary, as according to the situational description they just had started their career.

Translated into English. The scales used in the study were in German.

References

Adler, P.S., and C.X. Chen. 2011. Combining creativity and control: understanding individual motivation in large-scale collaborative creativity. Accounting, Organizations and Society 36:63–85.

Aguilera, R., D.E. Rupp, C. Williams, and V. Ganapathi. 2007. Putting the S back in corporate social responsibility: A multi-level theory of social change in organizations. Academy of Management Review 32:836–863.

Aguinis, H. 2011. Organizational responsibility: Doing good and doing well. In APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, Vol. 3, ed. S. Zedeck, 855–879. Washington: APA.

Aguinis, H., and A. Glavas. 2012. What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: a review and research agenda. Journal of Management 38:932–968.

Aguinis, H., and A. Glavas. 2019. On corporate social responsibility, sensemaking, and the search for meaningfulness through work. Journal of Management 45:1057–1086.

Alexander, C.S., and H.J. Becker. 1978. The use of vignettes in survey research. Public Opinion Quarterly 42:93–104.

Anderson, C.A., A.J. Lindsay, and B.J. Bushman. 1999. Research in the psychological laboratory: truth or triviality? Current Directions in Psychological Science 8:3–9.

Backhaus, K.B., B.A. Stone, and K. Heiner. 2002. Exploring the relationship between corporate social performance and employer attractiveness. Business and Society 41:292–318.

Balakrishnan, R., G.B. Sprinkle, and M.G. Williamson. 2011. Contracting benefits of corporate giving: an experimental investigation. The Accounting Review 86:1887–1907.

Bauer, T.N., and L. Aiman-Smith. 1996. Green career choices: the influence of ecological stance on recruiting. Journal of Business and Psychology 10:445–458.

Brammer, S., H. He, and K. Mellahi. 2015. Corporate social responsibility, employee organizational identification, and creative effort. Group & Organization Management 40:323–352.

Carroll, A.B. 1979. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. The Academy of Management Review 4:497–505.

Carroll, A.B. 1991. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business Horizons 34:39–48.

Carroll, A.B. 2016. Carroll’s pyramid of CSR: taking another look. International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility 1:1–8.

Carroll, A.B., and K.M. Shabana. 2010. The business case for corporate social responsibility: a review of concepts, research and practice. International Journal of Management Reviews 12:85–105.

de Charms, R. 1968. Personal causation: The internal affective determinants of behaviour. New York: Academic.

Cheng, B., I. Ioannou, and G. Serafeim. 2014. Corporate social responsibility and access to finance. Strategic Management Journal 35:1–23.

Christensen, L.J., A. Mackey, and D. Whetten. 2014. Taking responsibility for corporate social responsibility: The role of leaders in creating, implementing, sustaining, or avoiding socially responsible firm behaviors. Academy of Management Perspectives 28:164–178.

Collier, J., and R. Esteban. 2007. Corporate social responsibility and employee commitment. Business Ethics: A European Review 16:19–33.

Davies, I.A., and A. Crane. 2010. Corporate social responsibility in small-and medium-size enterprises: investigating employee engagement in fair trade companies. Business Ethics: A European Review 19:126–139.

Deci, E.L., and R.M. Ryan. 2000. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behaviour. Psychological Inquiry 11:227–268.

Deci, E.L., R. Koestner, and R.M. Ryan. 1999. A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological Bulletin 125:627–668.

Dhanesh, G.S. 2012. The view from within: internal publics and CSR. Journal of Communication Management 16:39–58.

Dhanesh, G.S. 2014. CSR as organization-employee relationship management strategy: A case study of socially responsible information technology companies in India. Management Communication Quarterly 28:130–149.

Ehnert, I., S. Parsa, I. Roper, M. Wagner, and M. Muller-Camen. 2016. Reporting on sustainability and HRM: A comparative study of sustainability reporting practices by the world’s largest companies. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 27:88–108.

Eisenberger, R., and J. Cameron. 1996. Detrimental effects of reward: reality or myth? American Psychologist 51:1153–1166.

Eisenberger, R., W.D. Pierce, and J. Cameron. 1999. Effects of reward on intrinsic motivation—negative, neutral, and positive: comment on Deci, Koestner, and Ryan (1999). Psychological Bulletin 125:677–691.

Frey, B.S. 1997. Not just for the money: an economic theory of personal motivation. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Frey, B.S., and R. Jegen. 2001. Motivation crowding theory: a survey of empirical evidence. Journal of Economic Surveys 15:589–611.

Gagné, M., and E.L. Deci. 2005. Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior 26:331–362.

Gagné, M., J. Forest, M.-H. Gilbert, C. Aubé, E. Morin, and A. Malorni. 2010. The motivation at work scale: validation evidence in two languages. Educational and Psychological Measurement 70:628–646.

Gond, J.-P., A. El Akremi, V. Swaen, and N. Babu. 2017. The psychological microfoundations of corporate social responsibility: A person-centric systematic review. Journal of Organizational Behavior 38:225–246.

Greening, D.W., and D.B. Turban. 2000. Corporate social performance as a competitive advantage in attracting a quality workforce. Business and Society 39:254–280.

Hur, W.-M., T.-W. Moon, and S.-H. Ko. 2018. How employees’ perceptions of CSR increase employee creativity: mediating mechanisms of compassion at work and intrinsic motivation. Journal of Business Ethics 153:629–644.

Ibrahim, N.A., J.P. Angelidis, and D.P. Howard. 2006. Corporate social responsibility: a comparative analysis of perceptions of practicing accountants and accounting students. Journal of Business Ethics 66:157–167.

Järlström, M., E. Saru, and S. Vanhala. 2018. Sustainable human resource management with salience of stakeholders: a top management perspective. Journal of Business Ethics 152:703–724.

Kim, C.H., and H. Scullion. 2013. The effect of corporate social responsibility (CSR) on employee motivation: A cross-national study. Poznań University of Economic Review 13:5–30.

Kim, S.-Y., and H. Park. 2011. Corporate social responsibility as an organizational attractiveness for prospective public relations practitioners. Journal of Business Ethics 103:639–653.

Klimchak, M., A.-K. Ward, M. Matthews, K. Robbins, and H. Zhang. 2019. When does what other people think matter? The influence of age. Journal of Business and Psychology 34:879–891.

Korschun, D., C.B. Bhattacharya, and S.D. Swain. 2014. Corporate social responsibility, customer orientation, and the job performance of frontline employees. Journal of Marketing 78:20–37.

Kramar, R. 2014. Beyond strategic human resource management: is sustainable human resource management the next approach? The International Journal of Human Resource Management 25:1069–1089.

Kunz, J. 2015. Objectivity and subjectivity in performance evaluation and autonomous motivation: An exploratory study. Management Accounting Research 27:27–46.

Kunz, J., and S. Linder. 2012a. Buy one, get one free: benefits of following the controllability principle for intrinsic motivation? In Performance measurement and management control: global issues, ed. T. Davila, M. Epstein, and J.-F. Manzoni, 339–362. Bingley: Emerald Group.

Kunz, J., and S. Linder. 2012b. Organizational control and work effort—Another look at the interplay of rewards and motivation. European Accounting Review 21:591–621.

Kuvaas, B., R. Buch, A. Weibel, A. Dysvik, and C.G.L. Nerstad. 2017. Do intrinsic and extrinsic motivation relate differently to employee outcomes? Journal of Economic Psychology 61:244–258.

Lee, E.M., S.-Y. Park, and H.J. Lee. 2013. Employee perception of CSR activities: Its antecedents and consequences. Journal of Business Research 66:1716–1724.

Lee, Y.-K., Y.S. Kim, K.H. Lee, and D. Li. 2012. The impact of CSR on relationship quality and relationship outcomes: A perspective of service employees. International Journal of Hospitality Management 31:745–756.

Lin, C.P., Y.H. Tsai, S.W. Joe, and C.K. Chiu. 2012. Modeling the relationship among perceived corporate citizenship, firm’s attractiveness, and career success expectation. Journal of Business Ethics 105:83–93.

Linder, S. 2010. Studying micro-level phenomena in strategic management: How ecologically valid are findings from vignette studies. Strategic Management Society Annual International Conference, Rom. working paper.

Lis, B. 2012. The relevance of corporate social responsibility for a sustainable human resource management: an analysis of organizational attractiveness as a determinant in employees’ selection of a (potential) employer. Management Revue 23:279–295.

Luce, R.A., A.E. Barber, and A.J. Hillman. 2001. Good deeds and misdeeds: A mediated model of the effect of corporate social performance on organizational attractiveness. Business and Society 40:397–415.

Maon, F., A. Lindgreen, and V. Swaen. 2010. Organizational stages and cultural phases: A critical review and a consolidative model of corporate social responsibility development. International Journal of Management Reviews 12:20–38.

Margolis, J.D., and J.P. Walsh. 2003. Misery loves companies: rethinking social initiatives by business. Administrative Science Quarterly 48:268–305.

Morgeson, F.P., H. Aguinis, D.A. Waldman, and D.S. Siegel. 2013. Extending corporate social responsibility research to the human resource management and organizational behavior domains: A look to the future. Personnel Psychology 66:805–824.

Mozes, M., Z. Josman, and E. Yaniv. 2011. Corporate social responsibility organizational identification and motivation. Social Responsibility Journal 7:310–325.

Nelling, E., and E. Webb. 2009. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: the ‘virtuous circle’ revisited. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting 32:197–209.

Orlitzky, M., F.L. Schmidt, and S.L. Rynes. 2003. Corporate social and financial performance: a metaanalysis. Organization Studies 24:403–411.

Osterloh, M., and B.S. Frey. 2000. Motivation, knowledge transfer, and organizational forms. Organization Science 11:538–550.

Peterson, D.K. 2004. The relationship between perceptions of corporate citizenship and organizational commitment. Business & Society 43:296–319.

van Prooijen, A.-M., and N. Ellemers. 2015. Does it pay to be moral? How indicators of morality and competence enhance organizational and work team attractiveness. British Journal of Management 26:225–236.

Rupp, D.E., J. Ganapathi, R.V. Aguilera, and C.A. Williams. 2006. Employee reactions to corporate social responsibility: an organizational justice framework. Journal of Organizational Behaviour 27:537–543.

Rupp, D.E., R. Shao, D.P. Skarlicki, E.L. Paddock, T.Y. Kim, and T. Nadisic. 2013b. Corporate social responsibility and employee engagement: The role of self-autonomy and individualism. The Annual Conference of the Academy of Management, Orlando, FL. Academy of management proceedings.

Rupp, D.E., R. Shao, M.A. Thornton, and D. Skarlicki. 2013c. Applicants’ and employees’ reactions to corporate social responsibility: The moderating effects of first-party justice perceptions and moral identity. Personnel Psychology 66:895–933.