If you are an American between the ages of 14 and 49 reading this, there is a decent chance you have genital herpes and don’t know it. About 11.9 percent of Americans in that range have herpes simplex virus 2, or HSV-2, the kind most commonly associated with genital outbreaks, and most of them—more than 4 in 5, by some estimates—have no idea.

That’s partly because government health officials think we’re better off that way. In 2019, a herpes diagnosis still carries an intense stigma. There are more than 1,000 posts on Reddit, the online discussion forum, containing the words herpes and devastated. Perennial articles chronicle the months, or even years, it takes for people who test positive to regain their self-worth and begin dating or having sex again. That’s why the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention actually recommends against widespread screening for genital herpes. In addition to the risk of false positives, “the risk of shaming and stigmatizing people outweighs the potential benefits” of testing everyone, the agency says. Many doctors don’t include the test in a standard STI panel unless a patient shows symptoms. Since many people with HSV-2 have either no symptoms or very mild symptoms, the majority never seek treatment and are never diagnosed.

This points to the medical reality of genital herpes: It is, for the vast majority of people, no big deal. Along with the 11.9 percent with HSV-2, 47.8 percent of Americans in the 14-to-49 age range carry HSV-1, or “oral herpes,” which generally causes cold sores around the mouth but can also cause genital herpes. If you’ve had chickenpox, shingles, or mononucleosis, you’ve also been infected by another virus in the herpes family. For the people who do have symptoms from genital herpes, they’re generally no worse than, well, cold sores, only they’re not on your face. Genital herpes only causes complications in people with compromised immune systems, and when it does, they’re usually treatable. In short, herpes simplex is a common, generally harmless skin condition that happens to sometimes be spread sexually. Barry Margulies, an associate professor of biological sciences at Towson University, said he tells students that herpes viruses are “extremely common pathogens that have actually sort of evolved a fabulous coexistence with us”—because “in most cases, nobody ever knows they have them.”

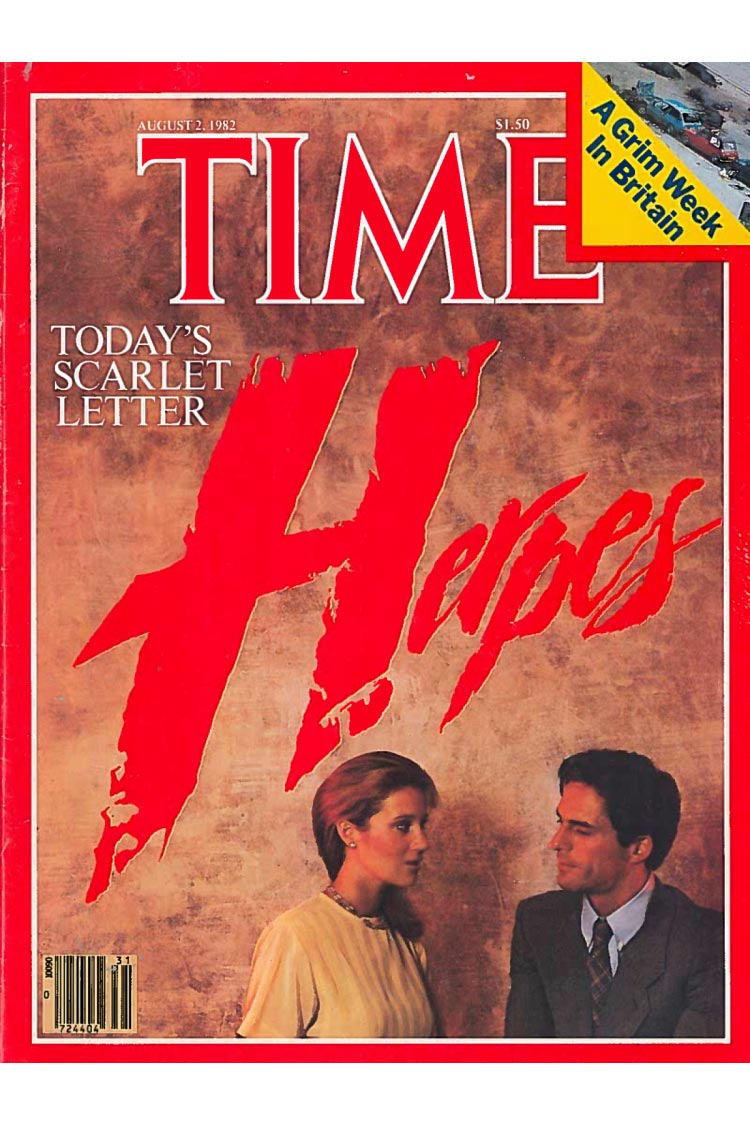

If herpes is such a minor deal, why does it come with such a pervasive stigma? In the first half of the 20th century, genital herpes was not on the public radar, and it wasn’t even recognized as a discrete type of herpes infection until the 1960s. But by the 1980s, it was slapped on the cover of Time with headlines like “Herpes: The New Sexual Leprosy.” What happened in the intervening years shows how a public sex panic is made. What’s still happening—herpes shame, fear, and confusion even now—shows how that panic can morph and persist. One of the oddest subplots of the stigma’s endurance has to do with who’s been falsely blamed for making herpes a boogeyman in the first place: drug companies.

Herpes simplex has been infecting hominids for millions of years, but it wasn’t until 1967 that scientists first distinguished between the HSV-1 and HSV-2 types, effectively creating the concept of “genital herpes.” The following year, a team of epidemiologists at Baylor University announced that it had found a correlation between herpes 2 and cervical cancer. (That link ultimately turned out to be a red herring; human papillomavirus, or HPV—not HSV-2—actually causes cervical cancer.) But even at the height of the sexual revolution, and with the specter of cancer attached to it, herpes 2 didn’t immediately infiltrate the public imagination. A 1973 article in the feminist magazine Off Our Backs quoted a doctor saying, “Such is herpes simplex, a common infection, barely a disease—so why talk about it?” In 1974, Abigail Van Buren, known as Dear Abby, reassured a reader, “My medical experts inform me that Herpes 2 should not (repeat not) be classified as a venereal disease,” since it can be spread nonsexually. “No need for you to be embarrassed,” she added. A 1976 New York Times Magazine story had an eminently reasonable conclusion: “For now, herpes viruses are part of our individual and collective ecosystems—like bacteria and pollution. We cannot get rid of them without getting rid of ourselves.”

But around the same time, many newspapers and magazines took a different approach. They called genital herpes an “epidemic” and emphasized that it was incurable and could result in dangerous neonatal infections when passed from mother to infant during childbirth. (Both are true, though the latter is exceedingly rare.) In 1973, Time gave readers this explanation of the difference between herpes 1 and 2 in an unbylined article: “Unlike the basic herpes simplex, which strikes indiscriminately, type II appears to exercise moral judgment—tending to afflict primarily the sexually promiscuous.” A 1978 Los Angeles Times article with the headline “Venereal Disease of New Morality: Sexual Sore Spot That’s Spreading” opened by describing two people with genital herpes so severe they required hospitalization and said that herpes was “roaring through parts of Orange County like an unwanted dinner guest.” In July 1980, Time again covered herpes under the headline “Herpes: The New Sexual Leprosy” and the subheadline “ ‘Viruses of love’ infect millions with disease and despair.” Later that year, Newsweek called herpes “an insidious venereal disease” and quoted someone with herpes saying, “It’s like someone putting a soldering iron against your skin.”

Herpes hysteria reached its pinnacle in 1982. The New York Times Magazine ran a story presenting the “evidence that the disease deals a terrible blow to the victim’s self-image.” Rolling Stone’s contribution to the genre that year was titled “Lovesick: The Terrible Curse of Herpes.” In August, Time ran a now-infamous cover story, “The New Scarlet Letter,” in which author John Leo dubbed herpes “the VD of the Ivy League and Jerry Falwell’s revenge.” The article claimed it was “altering sexual rites in America, changing courtship patterns, sending thousands of sufferers spinning into months of depression and self-exile and delivering a numbing blow to the one-night stand.” Abigail Van Buren changed her tune, encouraging readers to sanitize linens and tableware used by people with herpes and contradicting a reader who asserted that having genital herpes was “just like having a cold or the flu.”

Daniel Laskin, the journalist who wrote the New York Times Magazine’s 1982 story about the “evidence that [herpes] deals a terrible blow to the victim’s self-image,” wrote to me that his story was borne out of a hysteria that was in the air. “My feeling is that this atmosphere of panic (exaggerated, I guess, in retrospect) was a function of how media and culture worked,” he said.

Television also played an important role in terrifying Americans about herpes. In March 1981, 60 Minutes ran an episode on herpes. A CDC scientist named Mary Guinan, who appeared reluctantly in the episode, said it opened with the question “Dr. Guinan, which venereal disease would you least like to have?”—a question no one had ever actually asked her during the interview process. “The response that was aired was a contrived one, a sliced-together collage of clips discussing syphilis, gonorrhea, genital herpes, and orogenital sex,” Guinan wrote in her 2016 memoir. “I cringed.” According to Guinan, she was also roped into appearing on an episode of The Phil Donahue Show in which Donahue accused Guinan of “covering up” the herpes epidemic as the live studio audience heckled her. In 1983, ABC aired a made-for-TV movie called Intimate Agony in which practically everyone living in a fictional community called Paradise Island contracts herpes.

Why did herpes hysteria explode at this time? Modern researchers have estimated that the overall prevalence of herpes 2 rose from 13.6 percent to 15.7 percent between 1970 and 1985—just a modest increase. Around the same time, doctor visits for genital herpes increased tenfold, a fact that researchers at the time saw as evidence of an epidemic. But with the benefit of hindsight, the increase in doctor visits seems like evidence of something else.

“In the ’70s, there were many cultural concerns about sex and the fear of herpes,” said Allan M. Brandt, a professor of the history of medicine at Harvard University. “It was widely seen as untreatable, a persistent risk of infection, with long-term consequences.” It is likely that fear, not a rise of infections, drove the surge to doctors’ offices.

In the period in between the discovery of penicillin (which cured chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis) and the first reported cases of HIV/AIDS in 1981, Americans had no reason to think they were at much risk from casual sex—but they were deeply ambivalent about the idea of having multiple sex partners for fun. An incurable, easy-to-spread sexually transmitted infection that (sometimes) produced visible marks on the body and (very rarely) killed babies really did feel to some people like divine punishment for having sex. Indeed, a national survey commissioned in 1983 by Glamour found that 25 percent of women thought that “higher incidence of diseases transmitted through sexual intercourse … is God’s punishment for sexual promiscuity.” Billy Graham practically gloated about herpes as a sign of God’s displeasure with casual sex, saying, “We have the Pill. We have conquered VD with penicillin. But then along comes Herpes Simplex II. Nature itself lashes back when we go against God.” As one commentator for the New Republic wrote in 1982, “If herpes did not exist, the Moral Majority would have had to invent it.” Herpes was the perfect MacGuffin for a society ambivalent about the sexual revolution.

Ironically, one major contributor to the growing stigmatization of people with herpes may have been testimonials from people with herpes themselves, who skewed America’s sense of what a typical herpes diagnosis meant.

Oscar Gillespie, who co-founded a support group called HELP (Herpetics Engaged in Living Productively) in 1979, saw brief fame in the early 1980s when journalists started banging down his door asking for quotes about what it’s like to live with herpes. Gillespie appeared on The MacNeil/Lehrer Report, The Phil Donahue Show, Oprah, and 60 Minutes, and spoke to reporters from the New York Times Magazine and Time. “The mission was to get some clarity for what’s going on, for diagnosis and for treatment,” Gillespie told me over the phone. Nonetheless, some of the things he told the media sound pretty dramatic to modern ears. “People become murderous” upon being diagnosed with herpes, Gillespie said on PBS in 1982. “They want to take out contracts on the people that gave them herpes. And it often develops into a rather deep depression: ‘What will I do with my life? Now I am a leper; now I am left out of the normal swing of things.’ ”

From Gillespie’s perspective, he was simply relaying the feelings he’d heard from other people with herpes at support group meetings—and if reporters projected those feelings to a national audience, well, that was their job. “I didn’t create the language that was being used,” he told me. “I saw that language that was being used.” The word leper, Gillespie told me, “came from the people who had herpes. … If the media picked up on that, they’re just reporting.”

A major part of the herpes scaremongering of the late ’70s and early ’80s was that the infection was not merely incurable but also untreatable. When people went to their doctors with an outbreak, “They were told to go home and have a sitz bath and pretty much keep it clean and dry. That was pretty much it: keep it clean and dry,” Gillespie remembered. The lack of approved treatments for herpes didn’t stop some desperate patients—and some doctors—from experimenting. In 1981, the CDC issued a pamphlet warning people about the ineffectiveness of supposed treatments such as ether, dye-light therapy, and steroid creams.

Then, in March 1982, the Food and Drug Administration approved the very first treatment for genital herpes: an antiviral compound called acyclovir (brand name Zovirax), which was patented by Burroughs Wellcome, a private pharmaceutical company. Acyclovir had already been proven extremely effective as an intravenous treatment for immunosuppressed patients at high risk of developing complications from herpes simplex. Now it could treat genital HSV-2.

But as a treatment for genital herpes, the drug’s sales initial potential proved limited. It was FDA-approved only as a topical ointment, and only for an initial outbreak—there was insufficient evidence that it was effective for controlling recurrent outbreaks. By June 1983, the New York Times deemed Zovirax’s sales “disappointing.”

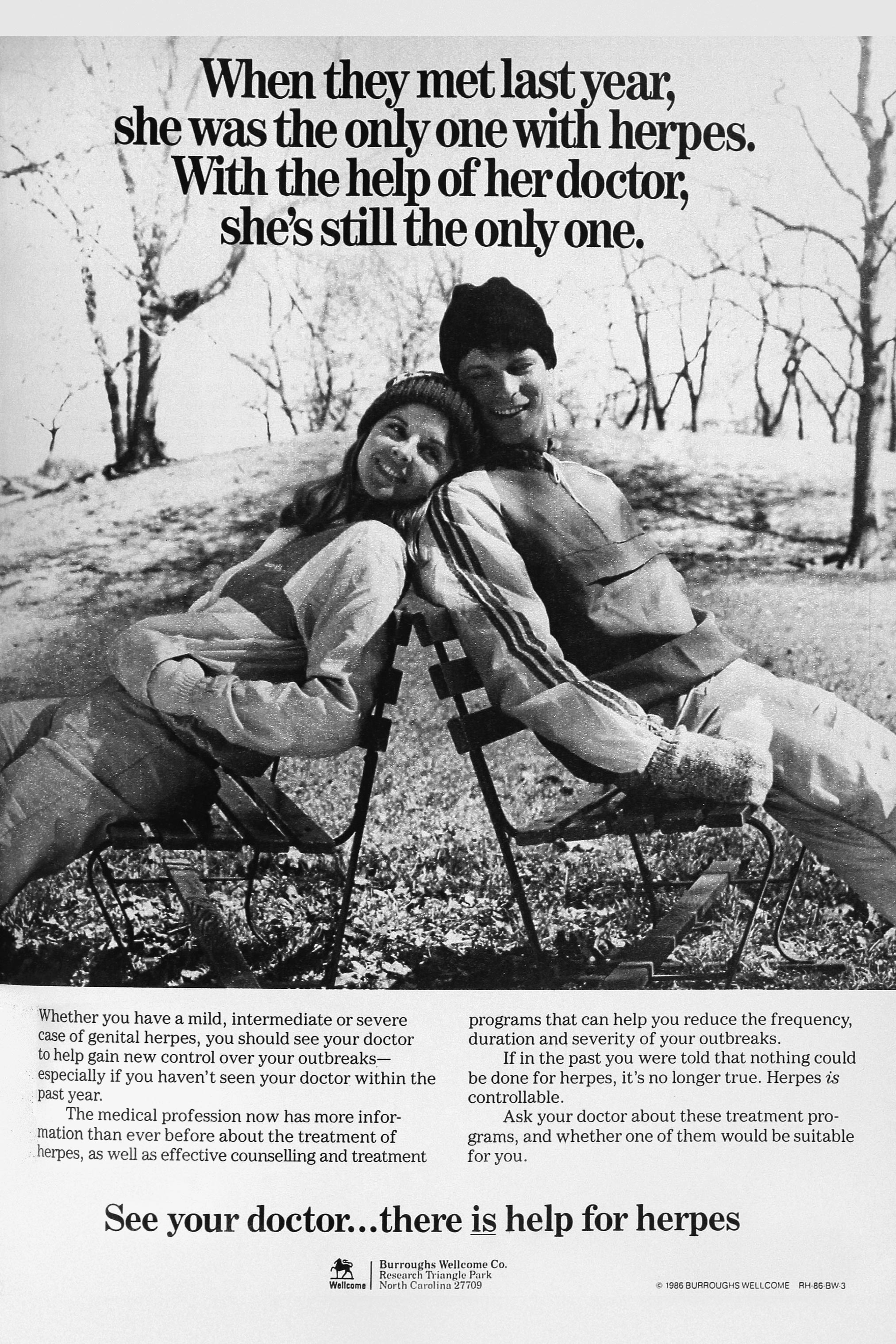

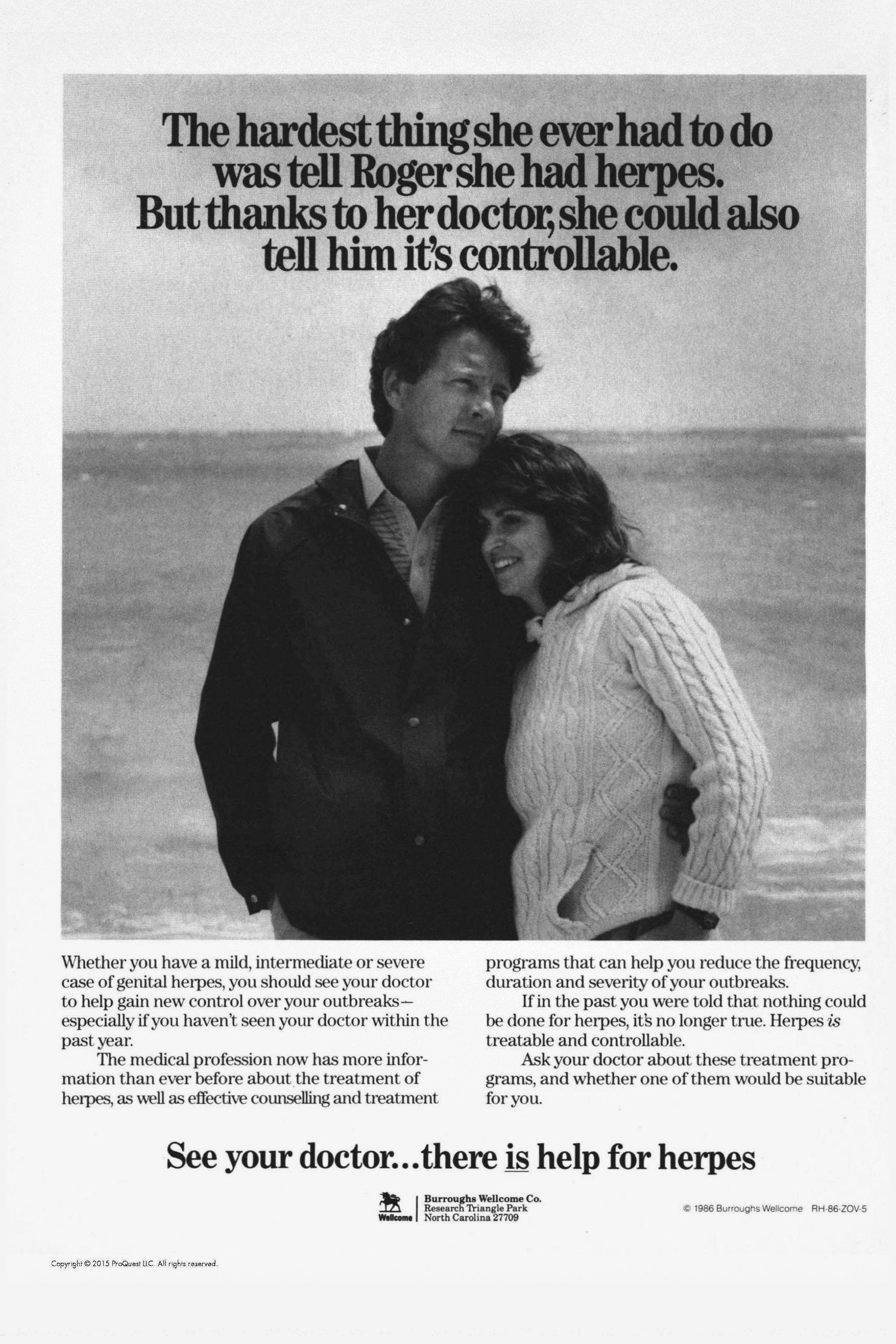

The tide turned for Burroughs Wellcome in January 1985, when the FDA approved an oral form of acyclovir to prevent or reduce the severity of recurrent herpes outbreaks. Burroughs Wellcome—unusually, at that time—launched an ad campaign in major magazines a few months later. These were what are known in the pharmaceutical industry as “help-seeking ads”—they didn’t mention Zovirax by name, but they informed readers that treatment was available for herpes and encouraged them to talk to their doctors about it. The ads ran in such publications as Cosmopolitan, Rolling Stone, People, and Playboy.

Zovirax was a medical breakthrough for the treatment of herpes simplex, chickenpox, and shingles, and one of its inventors was awarded a Nobel Prize in part for the drug. But it was also the source of the internet’s favorite conspiracy about how the herpes stigma was born. To hear some advocates for HSV-positive people tell it today, herpes didn’t carry any stigma until pharmaceutical companies, hellbent on selling their antiviral drugs, engineered a fearmongering campaign around it. “Herpes Genitalis, it seems, was not always stigmatized; it was merely a cold sore in an unusual place until the 1970s,” wrote an administrator for Project Accept, a nonprofit promoting herpes awareness and acceptance, in a frequently cited post. “The stigma is a comparatively recent phenomenon and appears to be the direct result of a Burroughs Wellcome’s Zovirax pharmaceutical marketing campaign in the late 1970’s through mid 1980’s.” The Herpes Viruses Association, a support group based in the U.K., has also promoted this hypothesis about the origins of herpes stigma.

This belief has gone mainstream: If you visited the Wikipedia page for herpes simplex any time between 2011 and earlier this year, you probably read a version of this theory. In recent years, it has been picked up by Vice (“Did Big Pharma Create the Herpes Stigma for Profit?”), Teen Vogue (“How Our Fear of Herpes Was Invented by a Drug Company”), and Salon (“How Big Pharma Helped Create the Herpes Stigma to Sell Drugs”). Or you might have heard it on the popular medical podcast Sawbones. It has comforted people newly diagnosed with herpes and has repeatedly fascinated the “Today I Learned” crowd on Reddit. It is also almost certainly not true.

If Burroughs Wellcome did play a role in stoking herpes stigma in the 1980s, one would expect its consumer-facing ads to play up the fears swirling around herpes. But the company’s campaign seemed designed to counter those fears. The ads showed attractive straight white couples embracing on the beach and lounging in natural settings. “The hardest thing he ever had to do was tell Sally he had herpes. But thanks to his doctor, he could also tell her it’s controllable,” read one tagline over a picture of one of these couples. “When they met last year, she was the only one with herpes,” read another. “With the help of her doctor, she’s still the only one.” The implication of these ads—on top of the crucial, sales-bolstering point that “herpes is controllable”—is that herpes is not a social death sentence, and people with herpes aren’t doomed to be eternally rejected by potential romantic partners. It’s a far cry from “the new sexual leprosy.”

“The intent is to encourage people with herpes to visit their physician,” said a Burroughs Wellcome spokeswoman at the time, because herpes “had a reputation for being an untreatable, incurable disease.” Indeed, it’s hard to read the Burroughs Wellcome ads from this era as creating herpes stigma—they were clearly in conversation with a stigma that was already there.

And in fact by the time its ads appeared, America’s hysteria about herpes had already begun to die down. Gillespie, the onetime favored herpes spokesman, thinks journalists changed their approach to talking about herpes after acyclovir arrived. “The hyperness of the media changed,” he said. “The media were not pushing the issue or talking to people about their fears anymore. … Once there was treatment, they didn’t need to do a 60 Minutes.” The New York Times agreed, running an article under the headline “ ‘Paranoia’ Over Herpes Seems to Subside” in September 1985. In the article, Dena Kleiman interviewed an unnamed biology professor who was diagnosed with herpes in 1983 and initially thought of himself as a “leper” and an “unclean person.” Upon successful treatment with oral acyclovir, the biology professor “said he felt better about himself.”

The other reason paranoia over herpes subsided in the mid-1980s was rising awareness about AIDS, a sexually transmitted infection that, unlike herpes, actually threatened people’s lives. “AIDS seems to have put herpes in perspective,” a gynecologist told Kleiman. “Herpes is an annoying illness, but it is hardly a catastrophe.”

Still, if herpes stigma is much different today than it was in 1980, it clearly endures, as all those anonymous testimonials show. So does an inability to accept the facts about the infection. And with that has come the desire for someone to blame.

That seems to be where the often-repeated theory that herpes stigma was mass-produced by a profit-hungry pharma company come from. Today the conspiracy greets anxious people with new diagnoses when they search for herpes on Google, and it speaks to an appetite to expose dark corporate skullduggery.

The main evidence—the smoking gun cited over and over again—seems to be a few sentences in a 2006 article in the Journal of Clinical Investigation by former Burroughs Wellcome research and development director Pedro Cuatrecasas. He writes:

During the D&D of acyclovir (Zovirax), marketing insisted that there were ‘no markets’ for this compound. Most had hardly heard of genital herpes, to say nothing about the common and devastating systemic herpetic infections in immunocompromised patients. But those with knowledge of clinical medicine knew that these were very serious and prevalent conditions for which there were no other therapies. Fortunately, at the time, research management had the authority and knowledge to render decisions.

Based on this passage, Project Accept concluded that “any public perception of need for antivirals” “would have to be manufactured.” Cuatrecasas’ article was also cited on the Wikipedia page for herpes simplex as evidence of a pharmaceutical conspiracy for several years. In February 2011, a Wikipedia editor named Marian Nicholson—also the director of the U.K.’s Herpes Viruses Association—added a section that read, “Genital herpes simplex was not always stigmatised. It was merely a cold sore in an unusual place until the 1970s.” Nicholson included a few snippets from Cuatrecasas’ article followed by the hypothesis, “Thus marketing the medical condition—separating the ‘normal cold sore’ from the ‘stigmatized genital infection’ was to become the key to marketing the drug.”

What exactly did Cuatrecasas mean when he wrote that Burroughs Wellcome’s marketing department “insisted that there were ‘no markets’ ” for acyclovir?

“During that time, certainly the condition was well-known,” he told me over the phone. “But there were no data provided in terms of incidence or prevalence or contagiousness.” Unlike with chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis, health care providers have never been required by law to report herpes diagnoses to their state and local health departments, and so accurate data on its prevalence was hard to come by in the ’70s and ’80s. (Today, the CDC’s data on the prevalence of herpes comes from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.) Burroughs Wellcome’s marketing team, Cuatrecasas recalled, “couldn’t get a hold of data. There were no data banks they could access. This is not atypical. … Most marketing people then, and it’s maybe even worse now, are not very imaginative.”

I asked Cuatrecasas whether there was anything to the belief that Burroughs Wellcome helped create herpes stigma. “No, no, not at all,” he replied. “No, that is really a conspiracy theory.” During clinical trials for acyclovir, Cuatrecasas added, Burroughs Wellcome was the one hearing from genital herpes patients desperate to try the drug. “There were people with severe, really severe fever blisters we don’t see much anymore.”

If you buy the conspiracy, you might be thinking that this is exactly what a pharmaceutical researcher would say to cover his tracks. But Cuatrecasas certainly didn’t sound like someone who’s a diehard supporter of his former employer. He said that after he left the company in 1985, he watched Burroughs Wellcome “jack up the price” of treatments for conditions in a way he found “unconscionable.”

I learned more about the company’s drug-promotion strategy from a former staffer named John Grubbs. Grubbs pitched doctors on Zovirax and other Burroughs Wellcome drugs for several years starting in 1987 and worked in the pharmaceutical industry for 23 years total. Grubbs said that Burroughs Wellcome sometimes sent out promoters to start talking up certain conditions to doctors before it released drugs to treat them—but never more than six months in advance. “They wouldn’t want to spend the money to have a sales force promoting something that may or may not come out,” Grubbs said. “You know, some drugs get to the very end and never end up getting approved.”

Like all pharmaceutical companies, Burroughs Wellcome was motivated by profit. There is evidence that it funded research to discredit other potentially viable herpes treatments in the ’80s, presumably to protect Zovirax’s market share. Over the years, the pharmaceutical beneficiary of these drugs also shifted: Burroughs Wellcome merged with Glaxo Laboratories in 1995, and Glaxo Wellcome then merged with SmithKline Beecham to become GlaxoSmithKline in 2000. In 2006, GlaxoSmithKline paid a doctor to promote the universal screening of pregnant women for herpes, a practice that’s not recommended by the CDC but would presumably increase demand for valacyclovir—brand name Valtrex—the second-generation herpes treatment that GlaxoSmithKline then had the patent for. Glaxo Wellcome’s patent on acyclovir had expired in 1997. (Valacyclovir remains popular as both a treatment for herpes outbreaks and as a viral suppressant for people who have herpes and partners who don’t.)

Project Accept’s 2012 article about the origins of herpes stigma is unbylined, and the organization’s current director didn’t respond to an email asking who wrote it. I did, however, exchange emails with Marian Nicholson. When I asked her why she thought that herpes stigma was invented by pharmaceutical companies, she claimed that “the newspaper and magazine articles (Time ‘Scarlet Letter’ etc.) came about because of PR briefings from companies working for Glaxo-Wellcome and so the sudden interest in herpes just before the drug hit the market was not a coincidence.”

I asked Nicholson if she had any specific evidence that Burroughs Wellcome contributed to the media’s herpes hysteria in the ’70s and ’80s. “No, I know of no one who has published any private BW instructions to their PR company to ‘big up’ genital herpes so as to promote sales of” acyclovir, she replied, adding that she assumed “this was understood by the PR company to be ‘what we do’ and it did not need spelling out.”

I asked Laskin, the journalist who wrote the New York Times Magazine’s 1982 story about herpes, whether Burroughs Wellcome had anything to do with his story. “I had no contact at all with Burroughs Wellcome,” he replied.

I don’t begrudge Nicholson, or anyone else, their belief that Burroughs Wellcome invented herpes stigma in the ’70s and ’80s. It’s undeniably compelling. It’s compelling because it offers people with herpes an alternative way of thinking about the virus they’ve contracted. It’s compelling because it illuminates an indisputable truth: that beyond the basic biological facts, everything we think about any health condition is socially constructed.

And there are seeds of truth in this conspiracy theory. It’s true that researchers didn’t even distinguish between herpes type 1 and herpes type 2 until the late 1960s and that genital herpes wasn’t even considered a “venereal disease” until the 1970s. It’s true that herpes stigma had to be “manufactured.” But it wasn’t manufactured by a nefarious pharmaceutical company. It was manufactured by the interplay of media and consumers, a vicious cycle in which the media covered herpes sensationally, generating fear and interest from consumers, and that in turn generated more sensationalistic articles and TV news segments, and then more fear, the press and the public mirroring and stoking each other’s hysteria. People who were most affected by herpes became both a pawn in and further fuel for the panic. It’s impossible to point to a single moment in this cycle and say, “That’s when genital herpes became stigmatized.” But we can point to the phenomenon and see how misguided it was and how misguided its aftermath remains today. We can begin to free ourselves from the stories people told about herpes in the ’70s and ’80s, and start telling one another new stories about herpes instead—stories about how common it is, how trivial it usually is, and how it should be least among your fears when you have sex.