Practice Essentials

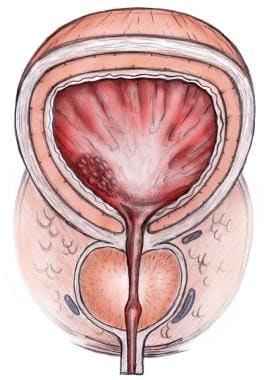

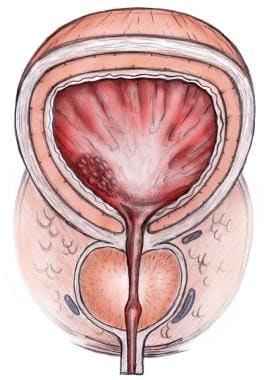

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), also known as benign prostatic hypertrophy, is a histologic diagnosis characterized by proliferation of the cellular elements of the prostate, leading to an enlarged prostate gland. Chronic bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) secondary to BPH may lead to urinary retention, impaired kidney function, recurrent urinary tract infections, gross hematuria, and bladder calculi. The image below illustrates normal prostate anatomy.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia. Normal prostate anatomy is shown. The prostate is located at the apex of the bladder and surrounds the proximal urethra.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia. Normal prostate anatomy is shown. The prostate is located at the apex of the bladder and surrounds the proximal urethra.

Signs and symptoms

When the prostate enlarges, it may constrict the flow of urine. Nerves within the prostate and bladder may also play a role in causing the following common symptoms:

-

Urinary frequency

-

Urinary urgency

-

Nocturia- Needing to get up frequently at night to urinate

-

Hesitancy - Difficulty initiating the urinary stream; interrupted, weak stream

-

Incomplete bladder emptying - The feeling of persistent residual urine, regardless of the frequency of urination

-

Straining - The need strain or push (Valsalva maneuver) to initiate and maintain urination in order to more fully empty the bladder

-

Decreased force of stream - The subjective loss of force of the urinary stream over time

-

Dribbling - The loss of small amounts of urine due to a poor urinary stream as well as weak urinary stream

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Digital rectal examination

The digital rectal examination (DRE) is an integral part of the evaluation in men with presumed BPH. With the DRE, the examiner can assess prostate size and contour, evaluate for nodules, and detect areas suggestive of malignancy.

Laboratory studies

-

Urinalysis - Examine the urine using dipstick methods and/or via centrifuged sediment evaluation to assess for the presence of blood, leukocytes, bacteria, protein, or glucose

-

Urine culture - This may be useful to exclude infectious causes of irritative voiding and is usually performed if the initial urinalysis findings indicate an abnormality

-

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) - Although BPH does not cause prostate cancer, men at risk for BPH are also at risk for this disease and should be screened accordingly (although screening for prostate cancer remains controversial)

-

Electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and creatinine - These evaluations are useful screening tools for chronic kidney disease in patients who have high postvoid residual (PVR) urine volumes; however, a routine serum creatinine measurement is not indicated in the initial evaluation of men with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) secondary to BPH [1]

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography (abdominal, renal, transrectal) is useful for helping to determine bladder and prostate size and the degree of hydronephrosis (if any) in patients with urinary retention or signs of kidney insufficiency. Generally, it is not indicated for the initial evaluation of uncomplicated LUTS.

Endoscopy of the lower urinary tract

Cystoscopy may be indicated in patients scheduled for invasive treatment or in whom a foreign body or malignancy is suspected. In addition, endoscopy may be indicated in patients with a history of sexually transmitted disease (eg, gonococcal urethritis), prolonged catheterization, or trauma.

IPSS/AUA-SI

The severity of BPH can be determined with the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS)/American Urological Association Symptom Index (AUA-SI) plus a disease-specific quality of life (QOL) question. Questions on the AUA-SI for BPH concern the following:

-

Incomplete emptying

-

Frequency

-

Intermittency

-

Urgency

-

Weak stream

-

Straining

-

Nocturia

Other tests

-

Flow rate - Useful in the initial assessment and to help determine the patient’s response to treatment

-

PVR urine volume - Used to gauge the severity of bladder decompensation; it can be obtained invasively with a catheter or noninvasively with a transabdominal ultrasonic scanner

-

Pressure-flow studies - Findings may prove useful for evaluating for BOO

-

Urodynamic studies - To help distinguish poor bladder contraction ability (detrusor underactivity) from BOO

-

Cytologic examination of the urine - May be considered in patients with predominantly irritative voiding symptoms

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Pharmacologic treatment

Agents used in the treatment of BPH include the following:

-

Alpha-adrenergic receptor blockers

-

5-alpha reductase inhibitors

-

Phosphodiesterase-5 enzyme inhibitors

-

Anticholinergic agents

Surgery

-

Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) - The criterion standard for relieving BOO secondary to BPH

-

Open prostatectomy - Reserved for patients with larege to very large prostates (>75 g), patients with concomitant bladder stones or bladder diverticula, and patients who cannot be positioned for transurethral surgery

-

Laparoscopic or robotric simple prostatectomy

Minimally invasive treatment

-

Transurethral incision of the prostate (TUIP) - For patients with prostates ≤ 30 g

-

Laser treatment - Used to vaporize or cut prostate tissue; multiple laser types are available, including GreenLight, holmium, and thulium; each has its own strengths and weaknesses

-

Water vapor thermal therapy (Rezum) - For prostate volume 30-80 g; high likelihood of preserving erectile and ejaculatory function

-

Robotic waterjet ablation therapy (Aquablation) - For prostate volume 30-80 g

-

Prostatic urethral lift (PUL): For prostate volume of 30-80 g and no obstructive middle lobe; high likelihood of preserving erectile and ejaculatory function

-

Prostate artery embolization - Performed by a radiologist

-

Temporary implanted prostatic devices (TIPD) - For prostate volume 25-75 g and absence of an obstuctive median lobe

-

Transurethral microwave therapy (TUMT) and transurethral needle ablation (TUNA) - Legacy technologies that have largely been displaced by newer minimally invasive technologies

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), also known as benign prostatic hypertrophy, is a histologic diagnosis characterized by proliferation of the cellular elements of the prostate. Cellular accumulation and gland enlargement may result from epithelial and stromal proliferation, impaired preprogrammed cell death (apoptosis), or both.

BPH involves the stromal and epithelial elements of the prostate arising in the periurethral and transition zones of the gland (see Pathophysiology). The hyperplasia presumably results in enlargement of the prostate that may restrict the flow of urine from the bladder.

BPH is considered a normal part of the aging process in men and is hormonally dependent on testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT) production. An estimated 50% of men demonstrate histopathologic BPH by age 60 years. This number increases to 90% by age 85 years.

The voiding dysfunction that results from prostate gland enlargement and bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) is termed lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). It has also been commonly referred to as prostatism, although this term has decreased in popularity. These entities overlap; not all men with BPH have LUTS, and likewise, not all men with LUTS have BPH. Approximately half of men diagnosed with histopathologic BPH report moderate-to-severe LUTS.

Clinical manifestations of LUTS include urinary frequency, urgency, nocturia (awakening at night to urinate), decreased or intermittent force of stream, or a sensation of incomplete emptying. Complications occur less commonly but may include acute urinary retention (AUR), impaired bladder emptying, the need for corrective surgery, kidney failure, recurrent urinary tract infections, bladder stones, or gross hematuria. (See Presentation.)

Prostate volume may increase over time in men with BPH. In addition, peak urinary flow, voided volume, and symptoms may worsen over time in men with untreated BPH (see Workup). The risk of AUR and the need for corrective surgery increases with age.

Patients who are not bothered by their symptoms and are not experiencing complications of BPH should be managed with a strategy of watchful waiting. Patients with mild LUTS can be treated initially with medical therapy. Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) is considered the criterion standard for relieving bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) secondary to BPH. However, minimally invasive therapies to accomplish the goal of TURP while avoiding its adverse effects are gaining wide use [2, 3] (see Treatment).

Anatomy

The prostate is a walnut-sized gland that forms part of the male reproductive system. It is located anterior to the rectum and just distal to the urinary bladder. It is in continuum with the urinary tract and connects directly with the penile urethra. It is therefore a conduit between the bladder and the urethra. (See the image below.)

Benign prostatic hyperplasia. Normal prostate anatomy is shown. The prostate is located at the apex of the bladder and surrounds the proximal urethra.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia. Normal prostate anatomy is shown. The prostate is located at the apex of the bladder and surrounds the proximal urethra.

The gland is composed of several zones or lobes that are enclosed by an outer layer of tissue (capsule). These include the peripheral, central, anterior fibromuscular stroma, and transition zones. BPH originates in the transition zone, which surrounds the urethra.

Pathophysiology

Prostatic enlargement depends on the potent androgen dihydrotestosterone (DHT). In the prostate gland, type II 5-alpha-reductase metabolizes circulating testosterone into DHT, which works locally, not systemically. DHT binds to androgen receptors in the cell nuclei, potentially resulting in BPH.

However, the fact that serum testosterone levels decrease with age, yet the development of BPH increases, suggests that other agents play an etiologic role. Possible factors include the metabolic syndrome, hyperinsulinemia, norepinephrine, angiotensin II, and insulin-like growth factors. [4] Increasing evidence indicates a role for autophagy (self-phagocytosis), the process by which cells degrade their cytoplasmic proteins and damaged organelles via lysosomes, in reducing apoptosis of prostate cells. [5]

In vitro studies have shown that large numbers of alpha-1-adrenergic receptors are located in the smooth muscle of the stroma and capsule of the prostate, as well as in the bladder neck. Stimulation of these receptors causes an increase in smooth-muscle tone, which can worsen LUTS. Conversely, blockade of these receptors (see Treatment) can reversibly relax these muscles, with subsequent relief of LUTS.

Microscopically, BPH is characterized as a hyperplastic process. The hyperplasia results in enlargement of the prostate that may restrict the flow of urine from the bladder, resulting in clinical manifestations of BPH. The prostate enlarges with age in a hormonally dependent manner. Notably, castrated males (ie, who are unable to make testosterone) do not develop BPH.

The traditional theory behind BPH is that, as the prostate enlarges, the surrounding capsule prevents it from radially expanding, potentially resulting in urethral compression. However, obstruction-induced bladder dysfunction contributes significantly to LUTS. The bladder wall becomes thickened, trabeculated, and irritable when it is forced to hypertrophy and increase its own contractile force.

This increased sensitivity (detrusor overactivity), even with small volumes of urine in the bladder, is believed to contribute to urinary frequency and LUTS. The bladder may gradually weaken and lose the ability to empty completely, leading to increased residual urine volume and, possibly, acute or chronic urinary retention.

In the bladder, obstruction leads to smooth-muscle-cell hypertrophy. Biopsy specimens of trabeculated bladders demonstrate evidence of scarce smooth-muscle fibers with an increase in collagen. The collagen fibers limit compliance, leading to higher bladder pressures upon filling. In addition, their presence limits shortening of adjacent smooth muscle cells, leading to impaired emptying and the development of residual urine.

The main function of the prostate gland is to secrete an alkaline fluid that comprises approximately 70% of the seminal volume. The secretions produce lubrication and nutrition for the sperm. The alkaline fluid in the ejaculate results in liquefaction of the seminal plug and helps to neutralize the acidic vaginal environment.

The prostatic urethra is a conduit for semen and prevents retrograde ejaculation (ie, ejaculation resulting in semen being forced backwards into the bladder) by closing off the bladder neck during sexual climax. Ejaculation involves a coordinated contraction of many different components, including the smooth muscles of the seminal vesicles, vasa deferentia, ejaculatory ducts, and the ischiocavernosus and bulbocavernosus muscles.

Epidemiology

BPH is a common problem that affects the quality of life in approximately one third of men older than 50 years. BPH is histologically evident in up to 90% of men by age 85 years. As many as 14 million men in the United States have symptoms of BPH. [6] Worldwide, there were 94 million prevalent cases of BPH in 2019, compared with approximately 51 million cases in 2000. [7]

The prevalence of BPH in White and African-American men is similar. However, BPH tends to be more severe and progressive in African-American men, possibly because of the higher testosterone levels, 5-alpha-reductase activity, androgen receptor expression, and growth factor activity in this population. The increased activity leads to an increased rate of prostatic hyperplasia and subsequent enlargement and its sequelae.

Prognosis

In the past, chronic end-stage BOO often led to kidney failure and uremia. Although this complication has become much less common, chronic BOO secondary to BPH may lead to urinary retention, chronic kidney disease, recurrent urinary tract infections, gross hematuria, and bladder calculi.

Patient Education

Patients should be informed that the following lifestyle changes may help relieve symptoms of BPH:

-

Avoid alcohol and caffeine

-

Avoid drinking fluids at bedtime; drink smaller amounts throughout the day

-

Avoid taking decongestant and antihistamine medications

-

Get regular exercise

-

Make a habit of going to the bathroom when theyhave the urge

-

Practice double voiding (empty the bladder, wait a moment, then try again)

-

Practice stress management and relaxation techniques

Patients should be warned that if they become unable to urinate, they are at risk for permanent kidney or bladder injury and need to go to a hospital emergency department.

For patient education information, see Enlarged Prostate (BPH) Symptoms, Diagnosis, Treatment.

-

Benign prostatic hyperplasia. Normal prostate anatomy is shown. The prostate is located at the apex of the bladder and surrounds the proximal urethra.

-

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) diagnosis and treatment algorithm.

-

Benign prostatic hyperplasia. Basic management of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in men.

Tables

What would you like to print?

- Overview

- Presentation

- DDx

- Workup

- Treatment

- Approach Considerations

- Alpha-Blockers

- 5-Alpha-Reductase Inhibitors

- Combination Therapy

- Phosphodiesterase-5 Enzyme Inhibitors

- Anticholinergic Agents

- Phytotherapeutic Agents and Dietary Supplements

- Transurethral Resection of the Prostate

- Minimally Invasive Treatment

- Open Prostatectomy

- Long-term Monitoring

- Prevention

- Show All

- Guidelines

- Medication

- Media Gallery

- References