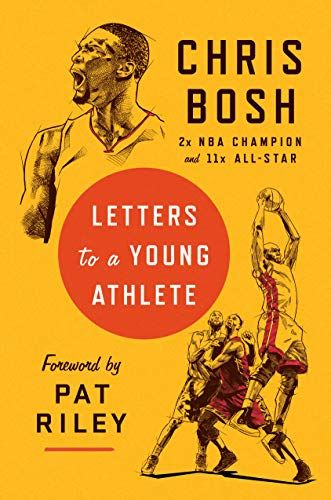

The following excerpt appears in 2021 Basketball Hall of Fame Inductee Chris Bosh's new memoir, Letters to a Young Athlete. In this essay, Bosh discusses how he confronted one of his biggest hurdles—the ego—and thinks back on memories of playing for the 2006 U.S. World Championship Team and the 2008 Olympic team.

It is being published exclusively on Men's Health courtesy of Penguin Random House.

I’m not saying you’re an egomaniac. But I’m saying you’ve got an ego.

I’m saying it’s a problem. It’s a problem for everyone.

Ego is that voice whispering in your ear.

Ego is that impulse to beat your chest and say, “I have nothing to learn from you”—from anyone.

Ego keeps you from passing the ball to a teammate because you want to be The Guy, not him.

Ego makes you think you know more than Coach.

Ego is the tempting voice that says, “I don’t need to show respect or kindness. I’m gonna go pro and get rich.”

Ego is what makes people say stuff like, “Do you even know who I am?”

Ego is the kid who quits the team because “Coach is out to get me.”

Ego is thinking that everyone you meet is a supporting player in the Story of You.

Ego is one of those things that’s hard to define exactly. But you know it when you see it.

And it’s never something good to see in your coaches, your teammates, or your friends. It’s what makes coaches yell at kids for no reason. It’s what turns promising young players into ball hogs. It’s what makes people—on the court and off—act like jerks.

And what’s especially dangerous about ego is that, as easy as it is to see in other people, it’s really hard to see in the mirror. Ego could be distorting your life, your relationships, your game right now—and unless you’re really good at introspection, you’d have no idea.

In 2006, I was on the U.S. World Championship Team. It was the year we lost to Greece in the semifinals. It was not a proud moment in American sports history. But looking back, it wasn’t a proud moment in my life either. I was fully in the sway of my own ego. I mean, I wasn’t like full‑blown Kanye West with my ego, but it was holding me back.

All I was thinking about during that tournament was my own playing time. I was so pissed that I wasn’t getting my due. Over the course of the tournament, I played fewer than 14 minutes a game. For someone used to playing a starter’s minutes, and getting a starter’s stats, that stung. I wasn’t used to coming off the bench to contribute.

It should have been a highlight of my career, starter’s minutes or not. I was representing my country. I was playing alongside the best in the game. I could have learned a lot from them, if I had gotten my head out of my ass. At the very least, I could have enjoyed the free trip to Japan for the tournament, right? But instead, it was days of feeling sorry for myself. It was days fuming at my coaches for not appreciating me enough. Mostly it was just me, me, me. I wasn’t thinking about the team. I wasn’t thinking of contributing, of cheering for my teammates from the bench, or of playing my ass off in the minutes I did get. I wasn’t thinking of anything much but what I wanted. That’s what ego does.

Now, I never had a blowup with the coaches or my teammates. I kept my head down and said the right things in public. But humans are really, really good at reading each other’s hidden feelings—we’re social animals, and that’s what we’ve evolved to do. Anyone within five feet of me would have known instantly that I was pissed, that I wasn’t buying in, that I didn’t give a damn about the team’s success if I couldn’t get my minutes. And attitudes like that are contagious.

Did my lack of buy‑in hurt the team? Did it contribute to our failure? It’s impossible to say—but I can tell you that it didn’t help. I was part of the problem.

When I look back on my career, that’s a period I really regret. Maybe you can remember moments like that in your life. Where you were a little petulant or selfish, where you were taking value away from your team rather than adding it, where you were refusing to learn and improve because you were just feeling stub‑ born. Maybe you remember days where the best thing you could have done for your teammates was stay away.

I had to sit with the disappointment of 2006 for a long time, and I came to realize how my self‑centeredness hurt the team, even if they didn’t know it, and, on an even more basic level, kept me from enjoying my chance to play on the world stage. But that’s the thing about fighting your ego: The most powerful step to defeating it is learning to see it in the mirror. Once you realize the role ego plays in holding you back, you’ve taken a huge step toward beating it.

In 2008, I had my second chance: I was back on the national team for the Olympics, and this time my attitude was, “What‑ ever it takes to play. Whatever the team needs.” I told this story briefly in the last letter, on communication, but I think it’s worth unpacking here. It was one evening after training camp in Vegas. Coach K, our head coach, had had some wine at dinner; afterward he came up to me, and what he said specifically was, “Hey, we were watching film, and I saw you on a pick‑and‑ roll. And you had huge arms—they were so long!”

Coach K didn’t ask me to do anything, but what I heard was, “This is an opportunity. This is your chance to contribute.” He didn’t say, “You can be the star of this team.” He didn’t say, “I see you with the ball with the clock winding down.” No, he was talking about something humbler, and what I heard was that he was thinking about the role I’d play with the team, and if I worked to impress him in practice, I’d have a better shot at being a contributor. A couple of years earlier, I would have just heard the compliment and nothing else. Or I would have dismissed the compliment as not “appreciating” what I was capable of doing with the ball in my hands moving toward the basket. I wouldn’t have thought about what I needed to do to earn more minutes, because I would have just felt entitled to them. I wouldn’t have seen the crack in the door. And been humble enough to stick my foot in there.

And it made a difference. Dwight Howard was our starter, but I was the first one off the bench to replace him in our rotation. I led the team in rebounds. And we brought home the gold medal.

Now, acting as if we lost in 2006 because I was blinded by ego, or as if we won in 2008 because I learned how to contribute off the bench, would just be another way of making this story all about me, instead of about our team. We lost in 2006 and won in 2008 for a ton of reasons that had nothing to do with me. But as far as I’m concerned, the difference is this: In 2006, I was hurting the team, whatever the stats said. In 2008, I was helping, whatever the stats said. No one, not MJ, not Kobe, not LeBron, can win a championship or a gold medal by himself. But every member of a team has the ability to change his contribution from a minus sign to a plus sign. I’m proud of the fact that I was able to do that in 2008.

That’s the good news about ego. It’s never too late to fix it. If you screw up and hurt your team out of selfishness or frustration? OK, well, the inability to own that, apologize, and grow from the experience? That’s ego, too. But looking at your behavior with some awareness, taking responsibility, listening to feedback, and doing better next time? That takes humility. It also takes confidence. So don’t dwell. Don’t deny. Improve.